California Needs to Call Time-Out on Fracking

Damon Nagami is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, based in the organization’s Santa Monica office. He can be reached at dnagami@nrdc.org.

Editor’s Note

This month Western City presents three articles about hydraulic fracturing (fracking): an overview, the case for fracking and the case against. These articles are presented for informational purposes only. The views expressed represent the authors’ opinions and not the policies or positions of the League. Links to the companion articles appear at the end of this article.

Oil and gas drilling has expanded at a breakneck pace nationwide in recent years as a controversial extraction technique called hydraulic fracturing (fracking) — has allowed companies to reach previously inaccessible deposits.

Unfortunately, safeguards have not kept pace. The oil and gas industry is operating with unprecedented exemptions from bedrock federal laws to protect communities, health and the environment — the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and toxic waste laws.1 And states have failed to fill in those gaps. As a result, every community where fracking is taking place has become a battleground.

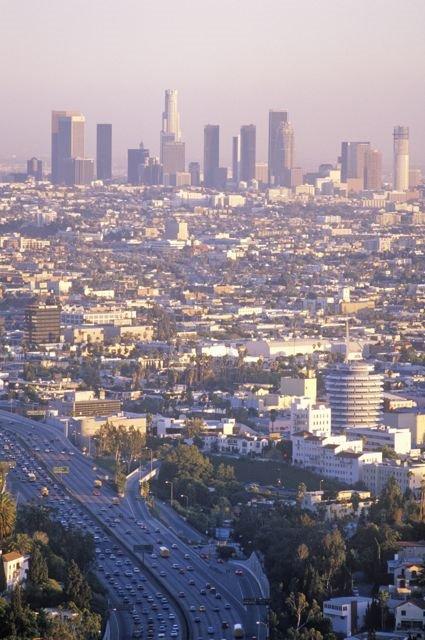

California is no exception. Millions here are living with the reality or threat of fracking or other harmful extraction methods in their communities. The threat is growing as oil companies look to further exploit the Monterey Shale Formation, which stretches hundreds of square miles from Northern to Southern California.

Yet, despite regulatory legislation the state passed last year, there are not sufficient safeguards to ensure California’s residents, drinking water, air and communities are protected. In fact, Californians still face uncertainty about where fracking is happening in the state.

The best path forward for California would be a statewide moratorium to give officials time to fully evaluate the risks and how to protect against them. That’s something polling shows a majority of Californians support. And it’s something the State of New York has already done.

Locals Act on Concerns About Water, Air and More

Unwilling to wait for the state to act, however, local governments are increasingly taking their fracking fate into their own hands. Joining a growing nationwide trend, California communities — from the cities of Los Angeles, Beverly Hills and Culver City, to Monterey, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz and San Benito Counties and more — have been exercising their local authority to restrict or halt fracking. Why? The reasons include concerns about water, air quality and seismic activity.

The state is in the midst of a crippling drought that has left water supplies so stressed it hinders the ability to fight wildfires and fracking is a water-intensive practice. Yet, industry downplays the amount of water California wells use by saying other parts of the country require even more to frack. That doesn’t ease concerns increased fracking could further strain already dwindling supplies here — especially when most of the water used in fracking is lost from the water cycle forever, according to reports from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, Downstream Strategies and San Jose State University.2 And fracking puts the state’s limited water supply at risk of contamination from explosive methane and cancer-causing chemicals. Americans all over the country have reported they can no longer use their well water — or worse, have gotten sick — after fracking moves in.3 Californians know we have to be extra careful with our limited water resources; this should give our leaders pause.

Fracking also adds to our air pollution problems.4 Of the dangerous substances emitted into the air from oil and gas production operations, chemicals referred to as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are the largest group and typically evaporate easily into the air. They are primarily found in oil and gas itself, but are also a byproduct of fuel combustion to operate pumps and engines and are found in chemical additives used in oil and gas production. Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, hexane, acrolein, acetaldehyde, and formaldehyde are common VOCs released during oil and gas production, according to a report from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Air Pollution Control Division.

Opening up new areas to fracking will bring harmful air contaminants to more backyards and communities. These contaminants have been linked to respiratory and neurological problems, birth defects and cancer.

In addition to these health concerns, scientists have confirmed that earthquakes caused by oil and gas production activities have been happening throughout the United States. The U.S. Geological Survey reports that earthquakes with a magnitude higher than 3.0 have increased significantly in the central and eastern United States in the past decade, with 450 quakes from 2010 to 2013, compared to a historical average of about 20 per year.5 If fracking-related quakes are rattling places like Oklahoma and Ohio, what could the impact be here? Even low-magnitude quakes can threaten critical infrastructure.

Despite all of the concerns, industry continues its campaign to gain access to the state’s oil while fighting real safeguards at every turn. Our leaders should not fall for it — especially when the potential benefits from fracking are speculative at best.

For one, the amount of recoverable oil in the Monterey Shale Formation, which has driven much of the hype to expand fracking in the state, remains uncertain. Once believed to hold as much as two-thirds of the country’s recoverable shale oil, federal officials downgraded their estimate in May 2014 by 96 percent — to roughly 32 days’ worth of oil. If this is accurate, it underscores the absurdity of rushing recklessly ahead.

Economic Benefits Overstated

Meanwhile, the industry’s claims of economic benefits are overstated. When five leading economists from the University of California (UC) Berkeley, UCLA, the University of Southern California and UC Santa Barbara reviewed an industry-backed report outlining alleged economic benefits from fracking, they found it had major flaws, including inflated job and state revenue predictions.6 This backs up what we’ve seen in other states: Fracking does not bring an influx of jobs to the local community. For the most part, crews of specialized experts are brought in from out-of-state to do the work. And the few jobs that are created locally are subject to the boom-and-bust cycle inherent in oil and gas development.

The real job-creating industries lie in the clean energy sector. Investments in clean energy create on average about six times as many jobs as investments in the fossil fuels sector. While the oil and gas industry laid off 10,000 workers during the recession, renewable energy companies added 500,000 jobs between 2003 and 2010. According to the Brookings Institution, the renewable energy industry has grown at twice the rate of the overall economy, and green jobs employ 2.7 million Americans — that’s more than the entire fossil fuels industry combined.

California’s oil demand is declining, thanks in part to our climate and sustainable communities laws. Regions across the state are adopting plans to invest in more transportation choices including transit, walking and biking, that can help reduce the need to drive. State and local incentives are putting more electric vehicles on the road, and we are working toward having 1 million electric vehicles on the roads in the next decade. This is the direction California and the nation must move.

California is at a crossroads. Our leaders can choose a path that endangers our families, our farmers, our drinking water, our sacred places, our coastal waters and our communities. Or they can prioritize clean energy sources — like energy efficiency, wind and solar and alternative fuels — that are already revitalizing rural communities and manufacturing towns nationwide. These are the energy sources that can power us safely into the future.

Footnotes

[1] See, e.g., http://www.nrdc.org/land/use/down/down.pdf

The following are some examples (this is not an exhaustive list).

Safe Drinking Water Act (pp. 14-15):

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) was enacted to protect public drinking water supplies as well as their sources. SDWA authorizes health-based standards for drinking water to protect against both naturally occurring and man-made contaminants. SDWA’s Underground Injection Control (UIC) program protects current and future underground sources of drinking water by regulating the injection of industrial, municipal and other fluids into groundwater, including the siting, construction, operation, maintenance, monitoring, testing and closing of underground injection sites. According to the EPA, there are more than 400,000 underground injection wells across the country used by agribusiness and the chemical and petroleum industries. (EPA, “What Is the UIC Program?” February 2006, http://www.epa.gov/safewater/uic/whatis.html.) The oil and gas industry, however, is exempt from crucial provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act intended to protect drinking water.

In 1997, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit ordered the EPA to regulate hydraulic fracturing under the SDWA after a hydraulic fracturing operation resulted in the contamination of a residential water well. (Legal Environmental Assistance Foundation v. United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 118 F.3d 1467 (11th Cir. 1997). This decision, however, was overridden by the Energy Policy Act of 2005.) In 2004, however, the EPA issued a study on hydraulic fracturing; it concluded that fracturing “poses little or no threat” to drinking water. This study was declared “scientifically unsound” by an EPA whistleblower. (Letter from Weston Wilson to Senators Allard and Campbell and Representative DeGette (8 October 2004), http://www.latimes.com/media/acrobat/2004-10/14647025.pdf.)

Clean Air Act (pp. 9-10):

First passed in 1970, and significantly amended in 1977 and again in 1990, the Clean Air Act limits emissions of nearly 190 toxic air pollutants known to be hazardous to human health by causing cancer, birth defects, reproductive problems, or other serious illnesses. Oil and gas production operations release many of these pollutants, such as benzene, toluene and xylene. The Clean Air Act established two programs to control these pollutants: one for major sources of the pollutants and a second for smaller sources.

The program to control major sources of hazardous pollutants established limits is called the National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAPs). To meet these standards, a company must install the maximum level of emission control of hazardous pollutants that is technically achievable by the cleanest facilities in an industry sector. Small sources of toxic air pollution that are under common control and are grouped together in close proximity to perform similar functions are required to be added together and considered as one source of emissions. If the aggregate emissions of these small sources meet the thresholds for major sources, then they must comply with NESHAPs. This “aggregation requirement” is intended to protect the public from smaller sources that might seem individually harmless but cumulatively account for the release of large volumes of toxic substances into the air.

The Clean Air Act completely exempts oil and gas exploration and production activities from this aggregation requirement. (42 U.S.C.§ 7412(n)(4)(A).) Even if wells, compressor stations, condensate tanks and disposal pits are adjacent to each other and owned by the same company, they do not have to comply with NESHAPs. For example, in Garfield County, Colorado, more than 30 tons of benzene are released into the air from 460 oil and gas wells. (Colorado Department of Health and Environment, Air Pollution Control Division, “Emission Inventory Data” (2004), http://emaps.dphe.state.co.us/APInv.) This is nearly 20 times more benzene than is released by a giant industrial oil refinery in Denver, yet none of the toxic emissions from these oil and gas wells are subject to NESHAPs.

Clean Water Act (p. 18):

The oil and gas industry now enjoys significant exemptions from the Clean Water Act’s stormwater permit requirements. Since 1987, oil and gas “operations” have not needed a stormwater permit as long as their stormwater discharges were uncontaminated. (33 U.S.C. § 1342(l)(2).) In the Energy Policy Act of 2005, Congress expanded this exemption to include the construction of new well pads and the accompanying new roads and pipelines. (Energy Policy Act of 2005, § 323.)

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (pp. 22-23):

Enacted in 1976 and significantly amended in 1980, RCRA sets standards for management of hazardous waste throughout its life cycle from cradle to grave — including generation, transportation, treatment, storage and disposal — in order to prevent harm to human health and the environment. These standards are a powerful incentive for a company to minimize waste and pollution through methods such as changing the industrial process and using substitute materials that are not hazardous. When Congress wrote RCRA, it gave the EPA the authority to determine whether the law should cover hazardous wastes associated with oil and gas exploration, development, or production. (42 U.S.C. § 6921(b)(2).) The EPA sampled drilling fluids and produced water at field sites and found pollutants at levels that exceeded 100 times the agency’s standards, including benzene, lead, arsenic and uranium. The agency found 62 documented cases where waste from oil or natural gas operations had endangered human health. The EPA also found that, while there were some federal and state regulations in place to control hazardous oil and gas wastes, there were some gaps as well as inadequate enforcement. (“Regulatory Determination for Oil and Gas and Geothermal Exploration, Development and Production Wastes,” 53 Fed. Reg. 25,446 (July 6, 1988). Ironically, the EPA stated that it would work to improve the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act to fill some of these gaps in environmental protection. Since then, the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act have actually been weakened by the creation of even more exemptions for the oil and gas industry.) EPA staff recommended that some hazardous oil and gas wastes be regulated, but they were overruled by senior agency officials in 1988 when the EPA exempted wastes uniquely associated with oil and gas exploration and production from RCRA’s hazardous waste provisions. At the time, the assistant to the EPA’s then-director of hazardous site control told a reporter, “This is the first time that in the history of environmental regulation of hazardous wastes that the EPA has exempted a powerful industry from regulation for solely political reasons, despite a scientific determination of the hazardousness of the waste.” (Dixon, J., “EPA Said To Bow To Political Pressure In Oil Wastes Ruling,” Associated Press, 19 July 1988.) The majority of exploration and production wastes are covered by this exemption (Puder, M.G. and J. A. Veil, “Offsite Commercial Disposal of Oil and Gas Exploration and Production Waste: Availability, Options and Costs,” Argonne National Laboratory, ANL/EVS/R-06/5 (August 2006), p. 74), and the list of exempt wastes includes drilling fluids, produced water, hydrocarbons, hydraulic fracturing fluids, sludge from disposal pits, drilling muds and sediment from the bottom of tanks. (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Exemption of Oil and Gas Exploration and Production Wastes from Federal Hazardous Waste Regulations,” p.10, www.epa.gov/epaoswer/other/oil/oil-gas.pdf.)

[2] See the 2012 GAO report: Energy Water Nexus: Information on the Quantity, Quality, and Management of Water Produced During Oil and Gas Production. It shows that 98 to 99 percent of produced water is disposed of by injection into Class II UIC wells. It’s not specific to flow back, but nationally the number should be reflective of all wastewater management. http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-156

See also, e.g.,http://www.downstreamstrategies.com/documents/reports_publication/marcellus_wv_pa.pdf

“In recent years, the most common option in many regions of the US is to pump waste fluids underground via underground injection control (UIC) wells. These wells are intended to dispose of waste far below ground, and the Safe Drinking Water Act regulates UIC use and operation.” (p. 7)

“Injected water that is not recovered is removed from the hydrologic cycle. Disposing of waste using UIC wells, which is becoming increasingly popular, also removes water from the hydrologic cycle.” (p. 37)

[3] http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/amall/incidents_where_hydraulic_frac.html

See also:

- The U.S. EPA has investigated reports of drinking water contamination in three places — Dimock, Pennsylvania; Pavilion, Wyoming; and Parker County, Texas — only to subsequently abandon their investigations without sufficient explanation and despite indications that the problems persist: http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/ksinding/why_would_epa_hide_info_on_fra.html

- The Pennsylvania Alliance for Clean Water and Air keeps a “List of the Harmed” nationwide, which includes residents by state & county and brief description of how they’ve been impacted. The list is currently more than 5,000 people long, with people reporting a range of impacts – including drinking water contamination & health impacts: https://pennsylvaniaallianceforcleanwaterandair.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/list-of-the-harmed55.pdf.

- The Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project is a regional nonprofit organization created solely to assist area residents who believe their health has been impacted by natural gas drilling activities. They list some reported health concerns in the region here: http://www.environmentalhealthproject.org/press-coverage

- This study links birth defects to fracking in Colorado: http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/122/1/ehp.1306722.pdf

- This short video was filmed during a National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) trip to meet with impacted people in Butler and Washington Counties in Pennsylvania. Among other things, residents here complain of getting sick and flammable water. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVR6fN1rzEg

- This article describes a man named George Zimmermann who sued Atlas Energy for contaminating the water and soil on his 480-acre property in Washington County, which contains a large heirloom tomato farm and a winery, with toxic chemicals from 10 wells they’ve drilled there. Water tests show his water was clean before the drilling, and that after it was fracked it contained seven potentially carcinogenic chemicals above EPA “screening levels.” http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/11/09/us-fracking-suit-idUSTRE5A80PP20091109

- This article describes an incident from Wetzel County, West Virginia, where Marilyn Hunt reported to the EPA in 2010 that: “frac drilling is contaminating the drinking water here.” Residents report health symptoms, such as rashes and mouth sores, as well as illness in their lambs and goats, which they suspect is linked to drinking water contamination.

- Two families in Butler & Washington County, Pennsylvania, suspect fracking is to blame for arsenic (among other things) in their drinking water: http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/amall/more_drinking_water_contaminat_1.html

- Diane Pitcock retired with her family to a farm in Doddridge County, West Virginia, with plans of canning vegetables and star-gazing. A self-described conservative, she knew her land had a conventional well on her property and wasn’t concerned. Then fracking moved to town. Now she has four rigs surrounding her land. She says her water developed a petroleum smell, and fracking companies have cleared acres of nearby woods for their operations. The noise and lights from nearby well-pads keep her up at night (it’s so bright she can read a book). Diane Pitcock formed a group called the West Virginia Host Farms, described as “a grassroots network of concerned landowners who provide journalists and scientists with access to their land in order to further research and media coverage of Marcellus Shale fracking.” She doesn’t think the issue should be politicized, saying “You can be pro-hunting or anti, or pro- or anti-gun, but you’ve still got to drink water, and you still need clean water and clean air to breathe.” This article tells her story. http://appvoices.org/2013/12/10/diane-pitcock-connects-landowners-to-fracking-researchers/.

Other articles:

Fracking Ourselves to Death in Pennsylvania (The Nation)

Residents of Wyoming Fracking Community Report Illnesses (NewsInferno)

In North Dakota and Nationwide, A Boom in Health Problems Accompanies Fracking (OnEarth)

Jury awards Texas family nearly $3 million in fracking case (LATimes)

Fracking Fallout in Ohio: ‘Throwing Up Until the Blood Vessels in My Eyes Burst’ (Yahoo! News)

[4] See, e.g., http://www.nrdc.org/land/use/down/down.pdf, pp. 8-13

Overview (p. 8): Of the dangerous substances emitted into the air from oil and gas production operations, chemicals referred to as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are the largest group and typically evaporate easily into the air. They are primarily found in oil and gas itself, but are also a byproduct of fuel combustion to operate pumps and engines and are found in chemical additives used in oil and gas production. Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, hexane, acrolein, acetaldehyde and formaldehyde are common VOCs released during oil and gas production. (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), Air Pollution Control Division, “Hazardous Air Pollutants from Oil and Gas Exploration and Production” (October 2006), http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/ap/uat/atoilgas.pdf.) VOCs pose health threats ranging from short-term illness to cancer or death. Other harmful VOCs that may be released include methanol (CDPHE, “Produced Water Evaporation Ponds, Emissions Estimates and Control Requirements” (31 May 2007)), triethylene glycol (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Compliance, “Profile of the Oil and Gas Extraction Industry” (October, 2000), p. 73, http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/publications/assistance/sectors/notebooks/oilgas.pdf) and a multitude of chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing. (CDPHE, Air Pollution Control Division, “Hazardous Air Pollutants from Oil and Gas Exploration and Production” (October 2006), http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/ap/uat/atoilgas.pdf.) VOCs react with sunlight to form ground-level ozone, or smog, which is known to be extremely hazardous to human health. Ozone can cause problems such as chest pain, coughing and throat irritation and can worsen bronchitis, emphysema and asthma. Recent studies have even linked ozone to premature mortality. (See generally: http://www.cleanairstandards.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/07/7-7-07-ozone-kills-fact-sheet.pdf.) Several Rocky Mountain counties with oil and gas production are already violating federal standards for ozone or are at risk of doing so.

[5] http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2014/3018/pdf/fs2014-3018.pdf

http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/bmordick/more_research_and_data_needed.html

This article appears in the September 2014 issue of Western

City

Did you like what you read here? Subscribe

to Western City