An Ocean of Opportunity

Don Benninghoven is chair of the Marine LIfe Protection Act (MLPA) Blue Ribbon Task Force and a former executive director of the League. Jim Dahl is mayor pro tem for the City of San Clemente and a member of the MLPA South Coast Regional Stakeholder Group. Leslie Daigle is a council member for the City of Newport Beach and member of the MLPA South Coast Regional Stakeholder Group.

The Marine Life Protection Act gives cities a tool to protect both economic and natural resources.

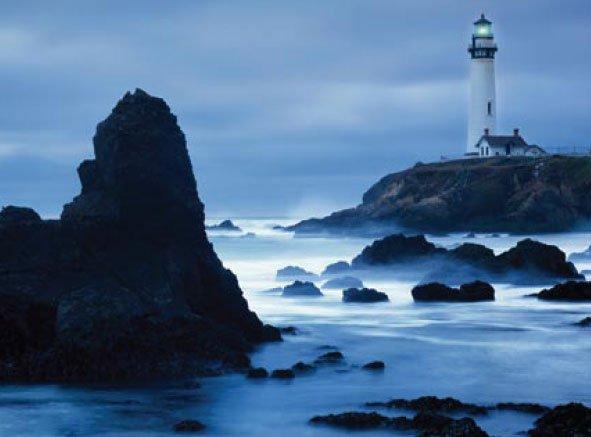

From Half Dome to the Hollywood sign, California is rich in iconic images. But nothing shouts “Golden State” more emphatically than the sight of its magnificent 1,100-mile coastline. The Pacific Ocean is California’s most recognized landmark — a mighty resource that endows residents with a signature way of life, while pouring more than $40 billion annually into the state’s economy.

The state Department of Parks and Recreation estimates that 75 percent of the state’s 36 million residents live within 30 miles of the ocean. Each year, more than 50 million people from all over the world visit California’s beaches. With numbers like these, it’s no surprise that California has the largest ocean economy in the nation, ranking first overall for both employment and gross state product.

Clearly there is a solid connection between California’s coastal assets and the state’s economic well-being. The past several decades, however, have witnessed a threat to these assets in the form of diminished habitat and marine species. Many of the fish that constitute the economic lynchpin of commercial fishing are at risk, dealing a devastating blow to the industry. As the state grapples with enormous budget deficits, a recession and severely limited funds for economic development, the need to sustain the Pacific’s crucial resources now has greater urgency.

Launching the Effort

Ten years ago, with both the environment and the economy on their collective minds, state legislators enacted the Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA), heralded as the first state law in the nation to establish a network of protected areas along the coast. Its intent was to take the existing hodgepodge of scattered reserves and create a well-designed and managed chain of protected marine ecosystems. With such an integrated network, California’s coastal waters could be saved from further degradation, diverse sea life could flourish, fish would become healthier and more plentiful and the state’s vital fishing industry could become more sustainable.

In theory, the MLPA concept is simple enough. But at the heart of the law are Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), and questions about the numbers and locations of these spots make implementing the MLPA quite challenging. No matter where they’re situated, MPAs have the potential to dramatically impact coastal residents, tourists, employers, fishermen and others.

To establish the MPAs, the state carved the California coastline into five regions (see “California’s Regions for Marine Protected Areas,” below). Within these regions, designated areas will become either:

- Marine reserves, where no fishing is allowed;

- Marine conservation areas, where some commercial and recreational fishing is permitted; or

- Marine parks, open only for recreational fishing.

Bringing People Together

Recognizing that any discussion of MPAs is likely to result in heated debate among various interest groups, the state Fish and Game Department devised a public decision-making process rarely seen in government circles; it offers total transparency and requires a meeting of minds between groups of historic adversaries.

“It’s a brave thing to do,” said Samantha Murray, ecosystem program manager for the Ocean Conservancy. “Getting environmentalists, fishermen, scientists, divers and wildlife enthusiasts to sit

down together and design a plan for MPAs in their coastal regions is very innovative; it puts results right in the hands of the stakeholders.”

Murray has been involved in the stakeholder group for the North Central Coast region of California since it was formed two years ago. This group is the second one to develop MPA proposals and submit them to the Blue Ribbon Task Force, which makes recommendations for approval to the state Fish and Game Commission. The commission will decide on a final proposal for the North Central region in August.

“At the beginning of our discussions, we had people in the group standing in a corner with their arms crossed,” said Murray. “In the end, we found middle ground.” According to Murray, the group had a compelling reason for working together. “We knew if we didn’t develop an MPA plan for ourselves, an agency would do it for us. It wasn’t easy — we had to rid ourselves of some stereotypes and get to know each other as people.”

Overcoming Obstacles

Over the course of about 18 months, Murray said, 60 public hearings were held, resulting in one proposal weighted toward fishermen, one toward environmentalists, and one that presented compromises for both factions. “No one gets everything they want in the compromise package,” Murray explained, “but it will protect most of the area’s special places and still leave favorite fishing spots open.”

One of the most remarkable examples of trust and collaboration to come out of the North Central stakeholder group concerned the Farallon Islands, a marine sanctuary off the coast of San Francisco and a particularly sensitive area for both environmentalists and fishermen. “No one in the group wanted to touch the Farallones,” said Jay Yokomizo, a charter boat operator from Emeryville, who noted that a compromise in that spot has always seemed out of reach.

“I knew there would be reserves there; rock cod fishing was already limited. But, still, I felt there had to be a way to keep certain areas open so fishermen could stay in business.” Yokomizo said he talked to commercial and recreational fishermen who fish for salmon and cod. He examined state guidelines; he exchanged ideas with Bob Wilson, a former board member from the Marine Mammal Center. Then the two men put their heads together and developed a plan for the Farallones that was ultimately accepted by the entire stakeholder group.

“It was very difficult,” said Yokomizo. “We’re giving up some great, fertile fishing areas that we’ll never see again, and commercial fishermen have already been hit with so many regulations. When they gave me the thumbs up, though, I felt that at least we had a plan everyone could live with.”

Reaching a Compromise

For the Central Coast stakeholder group — the first to offer MPA proposals to the Blue Ribbon Task Force — common ground proved more elusive. Group representatives sent three separate proposals to the task force, two favoring environmentalists, one emphasizing fishing interests. In the end, “everything was changed and merged,” said Steve Scheiblauer, harbor master for the City of Monterey. “When the approval came down, no one recognized the original proposals.” Critics of the final Central Coast MPA plan say it’s clearly partial to environmentalists. One reason, according to Scheiblauer, is because “the plan designates only 18 percent of state waters in the region as protected, but the net outcome is the loss of 45 percent of the rocky bottom structure, which is where most of the fish are.”

As the first stakeholder group to undertake the MPA process, the Central Coast gathering provided valuable lessons to others preparing to embark on their own missions. Many in the stakeholder group recognized the importance of bringing in as many fishermen and conservationists as possible. This reasoning proved sound, because the Blue Ribbon Task Force did sign off on a compromise proposal.

What’s Ahead

The public MPA process is now in full swing in Southern California, where the South Coast stakeholder group has been meeting since fall 2008. The North Coast and San Francisco Bay regions are set to begin the MPA public dialogue, with timelines through 2011.

The South Coast group’s efforts involve the region between Point Conception and the California-Mexico border. One member, Calla Allison, is a marine protection officer for the City of Laguna Beach. She’s watched the MPA process in the northern areas of the state, and she noted, “It’s a different animal down here, just with the sheer number of people we have using every inch of this coastline.”

One public hearing ran until 1:00 a.m. Allison said, “That’s an example of how strongly people feel about MPA issues; so many want their voices heard, and this is what is so exciting about this process. It’s arduous, but the longer it takes, the better the outcome. I’m so impressed by this perfect opportunity for a more participatory form of democracy.”

Equally impressive, said Allison, is the fact that the MPA process includes stakeholders from all backgrounds and interests. “It’s the people on the ground, doing the actual work, who are making policy.”

In the City of Laguna Beach, which attracts 5 million visitors each year, Allison stressed the importance of balancing both short- and long-term socioeconomic impacts of the MPAs. Cities, she said, should not see the MLPA as another state-mandated budget burden, but instead should enlist support from local groups and use existing code enforcement mechanisms to help monitor MPA goals. “This is a unique experience,” she observed. “We have the opportunity to set a model for California.”

Many people see that model extending much farther than the Pacific coast, according to Allison. “The whole world is watching to see what California does,” she said.

How the world views the process and results remains to be seen. Meanwhile, stakeholder groups up and down the coast are listening to and learning from each other in a concerted effort to protect California’s most critical marine resources far into the future.

California’s Regions for Marine Protected Areas

The state’s five regions for Marine Protected Areas are:

- North Coast — from the Oregon-California border to Alder Creek, near Point Arena;

- North Central Coast — from Alder Creek, near Point Arena, to Pigeon Point;

- San Francisco Bay — the waters within the bay;

- Central Coast — from Pigeon Point to Point Conception; and

- South Coast — from Point Conception to the Mexico border.

The Role of Education and Tourism

A key component of California’s Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) focuses on educational opportunities. In marine reserves and marine conservation areas, schools are taking advantage of opportunities to educate students about ocean sciences and the marine environment. Enthusiastic students share this information with parents, often spurring more extensive civic involvement by residents who want to preserve a healthy beach environment where their families can enjoy leisure time. In addition, educational activities spark an interest in the ocean for many young people, thus helping to foster the next generation of scientists and researchers — and help build communities whose citizens recognize the value and economic importance of supporting a healthy marine environment.

The educational and recreational resources and amenities associated with MPAs also attract tourists. Tourism is a powerful $40 billion economic engine in California, and with so few economic development tools available to local communities, this is one that demands attention. A healthy ocean is good for tourism and the economy, and that benefits all Californians.

This article appears in the July 2009 issue of Western

City

Did you like what you read here? Subscribe to Western City