Regulating Fracking in California: An Overview

Ed Wilson is assistant director of communications for the California Department of Conservation and can be reached at PAO@conservation.ca.gov.

Editor’s Note

This month Western City presents three articles about hydraulic fracturing (fracking): an overview, the case for fracking and the case against. These articles are presented for informational purposes only. The views expressed represent the authors’ opinions and not the policies or positions of the League. Links to the companion articles appear at the end of this article.

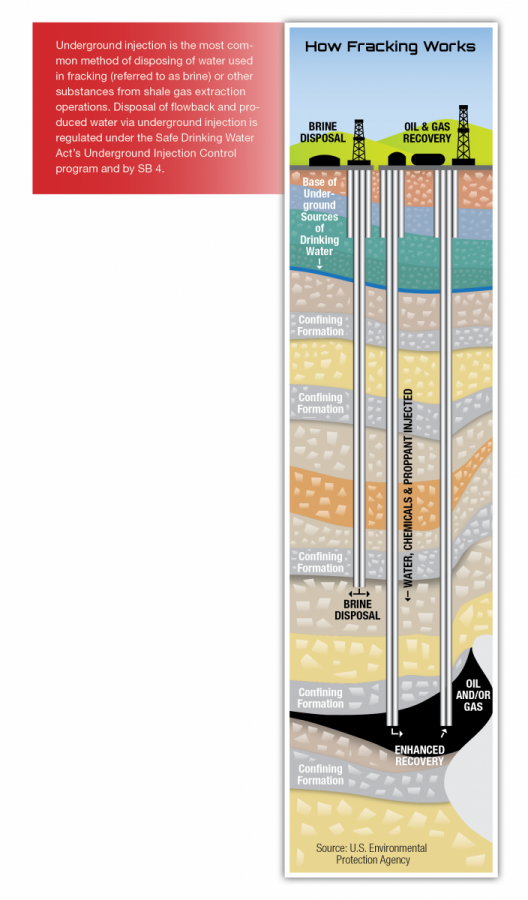

Hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, is a technique to enhance oil recovery. It involves injecting a mixture of water, small amounts of various chemicals and a “proppant” (often sand) at high pressure into a geologic zone. The oil and gas industry has used this process in various forms since the 1940s. As the name implies, that process fractures tightly packed strata and allows oil or natural gas to flow to a wellhead. The proppant helps keep the fractures open. The chemicals, which sometimes include acids, have various purposes, such as maintaining the viscosity of fluid, eliminating bacteria and preventing corrosion or scale deposits.

The oil and gas industry’s position is that the technique has allowed countless barrels of oil and cubic feet of natural gas to be produced that would otherwise have to be imported from foreign sources. But starting around 2010, concerned parties noted that in many places in the United States, the use of hydraulic fracturing was not specifically tracked or regulated.

The call for government at every level to take action spread quickly. It was particularly loud in California, home of both the environmental movement and an oil and gas industry established in the late 1800s; today the Golden State ranks third nationally in production.

While California had extensive oil and gas regulations and well-integrity requirements, the state did not specifically track or study hydraulic fracturing.

Legislation Addresses Call for Regulation

Eleven bills related to hydraulic fracturing or other well-stimulation techniques were introduced in the California Legislature in 2012. Of those, one became law: Senate Bill 4 (Chapter 313, Statutes of 2013), authored by state Senator Fran Pavley (D-27), who represents parts of Los Angeles and Ventura counties.

SB 4 went into effect Jan. 1, 2014. The law:

- Requires the Department of Conservation to adopt interim regulations to implement SB 4. Those regulations are currently in effect;

- Defines well-stimulation treatments, including hydraulic fracturing and acid matrix;

- Requires an independent scientific study of well stimulation to be commissioned by the Natural Resources Agency and conducted by the California Council of Science and Technology;

- Turns the use of well stimulation into an event that must be permitted by the Department of Conservation’s Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources as of Jan. 1, 2015. During calendar year 2014, operators must notify the division in advance of using well stimulation and self-certify that they are meeting the law’s requirements;

- Requires baseline and post-stimulation groundwater testing, groundwater and air quality monitoring and water management plans;

- Ensures transparency by requiring neighbor notification prior to the use of well stimulation and the posting of pre- and post-stimulation reports online that capture a wide variety of data, including water and chemical usage as well as any nearby earthquakes;

- Requires the Department of Conservation to work with a number of other concerned agencies — including the Department of Toxic Substances Control, the California Air Resources Board, the State Water Resources Control Board and local and/or regional air and water districts — to adopt rules and regulations specific to well stimulation;

- Requires the Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources to perform random periodic spot-check inspections during well-stimulation treatments;

- Requires the Department of Conservation to conduct an environmental impact report (EIR) on the statewide impacts of well-stimulation use; and

- Requires disclosure of the chemical composition of hydraulic fracturing fluid to the Department of Conservation, even if a trade secret is claimed.

SB 4 was designed to further protect public health and the environment by enhancing current oil and gas industry regulations. Some environmentalists, however, continue to seek a New York-style moratorium on hydraulic fracturing until further study is concluded.

“I think we ought to give science a chance before deciding on a ban on fracking,” Governor Jerry Brown told Bloomberg.com in October 2013, a month after signing SB 4 into law. “This is a very complicated equation. You can be sure that California is doing everything it can to reduce greenhouse gases and support a sustainable economy.”

Monterey Shale Estimates Downgraded

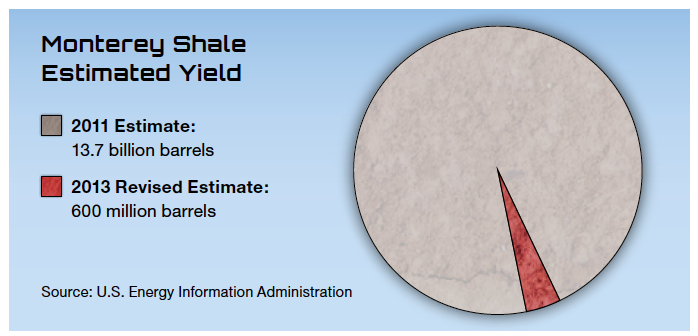

Much of the debate about hydraulic fracturing in California has focused on the Monterey Shale. That 1,750-square-mile formation — running from offshore to the Central Valley and from San Benito County in the north to northern Los Angeles County in the south — was said to hold about 13.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil in a 2011 report by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). A 2013 University of Southern California study estimated that the Monterey Shale oil boom could create nearly 3 million jobs and $25 billion a year in new taxes.

In mid-May 2014 the EIA released a new estimate on the Monterey Shale, bringing into question whether it is a bigger potential resource than the Marcellus Shale on the East Coast, the Bakken in North Dakota or the Eagle Ford in Texas. The EIA now estimates that only 600 million barrels — enough to cover U.S. consumption for about a month — can be recovered from the Monterey Shale with existing technology. The revised figure is 96 percent less than originally projected.

Unlike those other shale formations, the Monterey Shale is extensively faulted and folded, making things much more difficult for producers. Unlike the type of hydraulic fracturing in other parts of the United States that involve long horizontal wells with substantial water usage, California’s faulted geology makes horizontal wells much less common. The wells in California are primarily vertical wells that use far less water than wells in other states. A 2013 report by the nonprofit organization Ceres, which advocates for sustainability leadership, cites national averages of water use for fracking and states that vertical wells on average use about 85 percent less water than horizontal wells.

“From the information we’ve been able to gather, we’ve not seen evidence that oil extraction in this area is very productive using techniques like fracking,” EIA Petroleum Exploration and Production Analyst John Staub told the Los Angeles Times.

Some media pundits and environmental organizations responded to the EIA’s revised estimates for the Monterey Shale by renewing the call for a hydraulic fracturing moratorium: no big recover-able resource, no big payday, no need for a controversial production method.

“Regulators and oil producers alike consistently tried to downplay expectations for the short-term benefits of the Monterey Shale formation’s reserves,” Department of Conservation Chief Deputy Director Jason Marshall notes. “SB 4 was never just about the Monterey Shale. Well-stimulation techniques are used to produce oil and gas from a number of existing geologic formations in California.

“Now, there are a lot of people who would like to halt oil and gas production altogether and move toward other sources of energy,” says Marshall. “We understand that, and the Brown administration is a worldwide leader in encouraging the development and use of sustainable energy. As the state transitions to more sustainable energy, it is critical that we have adequate regulation in place to ensure that our existing oil and gas industry does not cause damage to the environment.”

The Department of Conservation held a series of public meetings both before and after issuing interim regulations supporting SB 4, which took effect on Jan. 1, 2014. It received, reviewed and responded to thousands of public comments. The department is currently fine-tuning the interim regulations into the permanent rules that will go into effect at the start of 2015. The public had additional opportunities to provide input on those permanent regulations in summer 2014.

“California is known worldwide for its leadership in environmental issues, and we are proposing these regulations with that legacy in mind,” Department of Conservation Director Mark Nechodom says. “They will supplement existing regulations that protect health, safety and the environment through strong well-construction standards. We believe that once the proposed regulations go into effect at the start of 2015, we will have in place the strongest environmental and public health protections of any oil- and gas-producing state in the nation, while also ensuring that a key element of California’s economy can maintain its productivity.”

Related Resources

Welcome to the Division of Oil, Gas & Geothermal

Hydraulic Fracturing in California Overview of Hydraulic Fracturing How Does Hydraulic Fracturing Typically Occur in California? California’s Well Construction Standards

U.S. EPA: Class II Wells – Oil and Gas-Related Injection Wells

The Fracker’s Quest: More Water

California Fracking Study May Take 18 Months, Brown Says

Improving Our Scientific Understanding of Hydraulic Fracturing

EPA’s study of hydraulic fracturing and its potential impact on drinking water resources: The EPA is undertaking a national study to understand the potential impacts of hydraulic fracturing on drinking water resources. The study will include a review of published literature, analysis of existing data, scenario evaluation and modeling, laboratory studies, and case studies. The EPA expects to release a final draft report for peer review and comment in 2014.

This article appears in the September 2014 issue of Western

City

Did you like what you read here? Subscribe

to Western City