Berkeley and Monterey’s awarding-winning infrastructure projects reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Brian Lee-Mounger Hendershot is the managing editor for Western City magazine; he can be reached at bhendershot@calcities.org.

Two innovative infrastructure projects from the cities of Berkeley and Monterey received top honors at the 2023 Outstanding Local Streets and Roads Project Awards. Berkeley won an award for the renovation of the “worst streets in town.” The award program recognized Monterey for its citywide adaptive traffic control system. Both projects resulted in a noticeable reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

Berkeley performs ‘open-heart surgery’ on ‘the worst roads in town’

Until recently, the city of Berkeley (pop. 124,321) was struggling with a battered street network that had a pavement condition index (PCI) score of 28. This was not just any stretch of streets. It is the sole connection to a group of hotels, restaurants, and recreational amenities on the Berkeley Marina that attract up to 300,000 visitors per year.

The PCI is divided into seven classes — with 0-10 categorized as failing. However, in practice, anything below 40 is considered near impassable.

“We basically had to do the work in different phases while keeping traffic going,” Supervising Civil Engineer Nelson Lam said. “It’s almost kinda like doing open heart surgery on a patient while keeping the patient alive.”

There were multiple attempts to repair the streets in the past. All of them failed due to what was under the road: a filled-in pier extension. No matter what the city did, the roadway kept shifting and sinking in between the pier caps, creating a series of unpleasant bumps. The roads were also at different heights, which resulted in chronic drainage problems.

Residents signaled their strong support for the reconstruction by approving a related bond measure. A major marina business provided 35% of the funding, with the remaining funding coming from SB 1 (Beall, 2017) and the county.

“Our businesses [and residents] at the marina have just been big champions of the idea that we’re going to improve things for them,” said Dee Williams-Ridley, the Berkeley deputy city manager. “The mayor and city council are also big champions of this project.”

In the end, the city did more than smooth the road. It moved the travel lanes off the old pier extension and turned the former roadway into a green space.

Moving an old road is as complicated as it sounds. Decades-old utilities are rarely where they are supposed to be, so service interruptions are an unavoidable challenge. The city also had to coordinate with two other municipalities, the East Bay Regional Park District and the California Department of Transportation, to finish the project. Both agencies had their own projects going on at the same time. The Berkeley Marina streets project had to be approved by the Bay Conservation Development Commission as well.

The new roads have several new features, including a roundabout that is identical to nearby, soon-to-be-completed roundabouts by Caltrans. Roundabouts require less maintenance than traditional intersections, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and improve safety for both drivers and pedestrians. Then there is the road itself, which was created with asphalt from the old roadway and has a permeable surface that allows stormwater to be treated before it flows into the ocean.

“Traditionally, you’ll see this type of installation in a handful of parking lots throughout the state,” said Scott Ferris, the director of the city’s Parks, Recreation & Waterfront Department. “We’re not absolutely sure, but this may be one of the first types of streets in California that has this type of storm drain installation.”

The improved network has several other notable elements, such as bioswales and bioretention basins with native pollinator plantings and access to other transportation options. Three of the network’s streets were improved, which now have a PCI score of 74. This puts it above the statewide average for local streets and roads.

The network is part of a larger, ongoing $45 million investment in the city’s waterfront. “This project is the spine that’s going to allow all those other projects to happen,” Ferris said. “Nelson has another eight to ten projects in the waterfront that he is working on [and] all of them will feed into this project in some shape or form.”

The project also received top marks from the Northern California Chapter of the American Public Works Association, which awarded it the Best Project of the Year and Best Project Between $5 and $25 million awards for 2022.

Monterey keeps traffic flowing and reduces emissions

The city of Monterey’s population (30,218) can swell to a service population of well over 100,000 on any given day — especially during a warm inland summer. Unsurprisingly, Monterey traffic can become unpredictable and frustratingly slow.

Like many cities, Monterey once relied on traditional time-of-day plans to coordinate its traffic signals. However, these plans are best guesses that become less reliable over time. Moreover, these plans cannot predict things like a global pandemic that completely changes how people drive. When these plans fail, complaints and greenhouse gas emissions go up and safety is degraded.

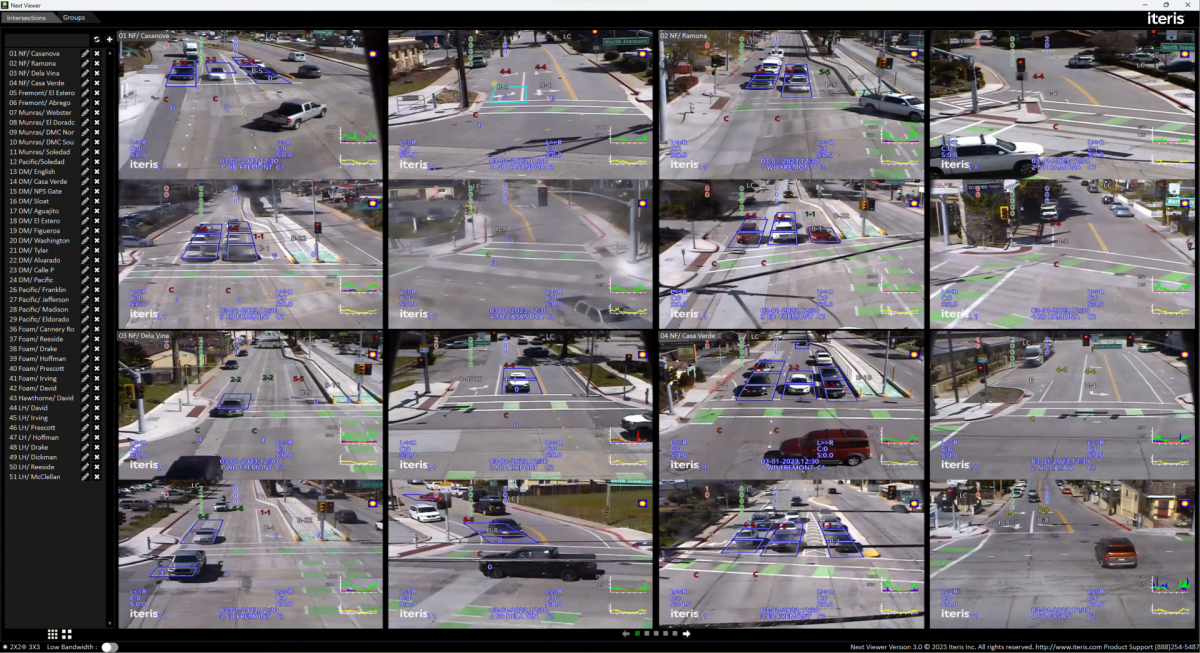

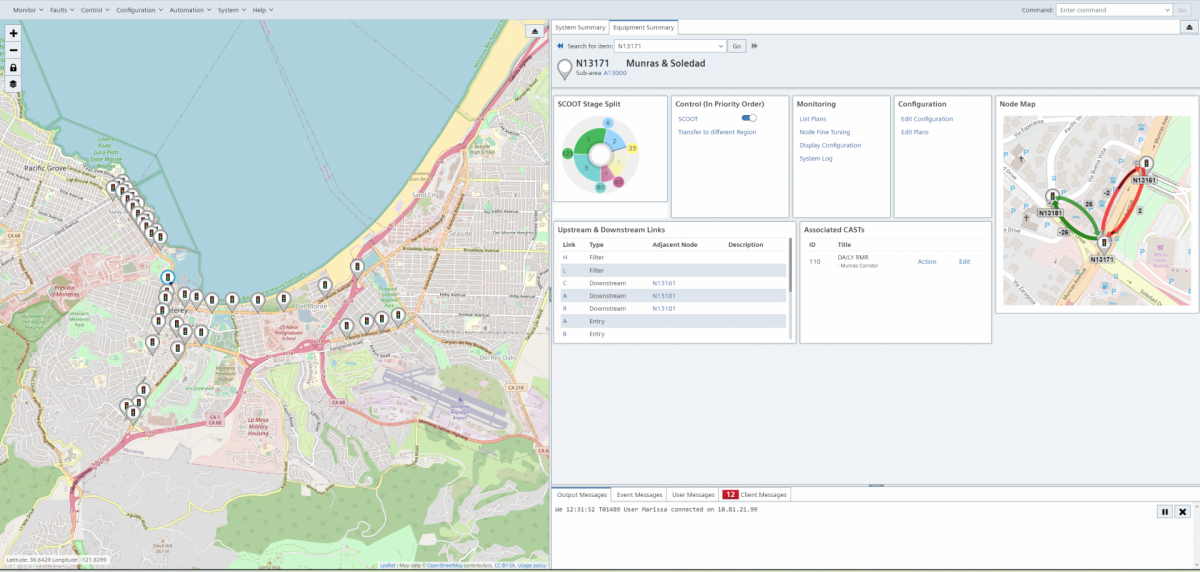

After years of research, the city found a solution: an adaptive traffic system called SCOOT. Each linked SCOOT traffic signal communicates traffic volumes and queues to a central server, which then adjusts individual signals to move groups of vehicles through a corridor with few or no stops. The system also uses historical data to predict traffic and staff can create different plans to help the system better respond to seasonal traffic patterns.

The system has been implemented on 41 of the city’s 56 arterial roads. When the project is completed, the system will control 51 traffic signals — an unusually high amount for a city of Monterey’s size.

“The remaining few signals are outliers,” said Marissa Garcia, the city’s engineering assistant. “They are not on the main corridors, so they don’t necessarily make sense to put on an adaptive system. The power with an adaptive system is really with the connectivity and corridor. It works best when it’s working in conjunction with others.”

The system is not completely automatic. Staff still need to make adjustments when traffic becomes extremely unruly. “It’s not magic. It does not make cars disappear,” Monterey Public Works Director Andrea Renny said. “When you have saturated flow, you still have congestion. But what SCOOT does really well is delay the onset of congestion and it also recovers more quickly from congestion.”

Still, the statistics are impressive. SCOOT has reduced the average travel time by 16%, delays by 30%, and stops by 40%. Since the system dramatically decreases idling and the resulting acceleration, vehicles burn less fuel and expel fewer pollutants and particulate matter. When fully implemented, the system will reduce criteria pollutants by 20 tons per year.

The system also proved its worth early in the COVID-19 pandemic. “If we had traditional time of day plans that assumed that our largest corridors were just going to carry the most traffic and take the most time, people on side streets would have a lot of unnecessary delays because our travel patterns just changed completely,” Renny said. “The peak times were different. The demands were very different than we normally see.”

The new system is part of a larger effort to make traveling through Monterey as pleasant as dipping your toes in the Pacific Ocean on a hot summer day. The city also has a robust transportation demand management program and is focused on building out a biking network that is safe and comfortable for people of all ages and skill levels.

Monterey’s adaptive traffic control system was also given the Clean Air Leader award for Technology by the Monterey Bay Air Resources District. The system is funded through the city’s Neighborhood Community Improvement Program, Monterey Bay Air Resources District and Regional Surface Transportation Program grants, and a special transportation tax measure.

Other winners and honorable mentions

Monterey and Berkeley were not the only winners this year. Stanislaus County received an award for its work on the new Tuolumne River Bridge. The vital connection between the city of Waterford and the community of Hickman was “scour critical and seismically deficient” before the new bridge. The project also included improvements to the adjacent Waterford River Park and River Park Trail and environmental mitigation efforts, such as homes for an estimated 6,000 bats.

Fresno County was recognized for its 14.5-mile sustainable pavement rehabilitation and Tehama County received an award for a bridge replacement project that runs over the Sacramento River. Honorable mentions include the cities of Montebello, San Jose, Manhattan Beach, Salinas, Santa Clarita, and Stockton; Orange County, and the San Diego Association of Governments.

The Outstanding Local Streets and Roads Project Awards are sponsored by the League of California Cities, County Engineers Association of California, and California State Association of Counties. Visit Save California Streets to view all the award-winning projects.