Career-Saving Tips on Mass Mailings

Question

Our agency has undergone a management transition. The new leadership believes strongly in community outreach — including keeping the community well informed and soliciting their feedback through questionnaires. I have been hired to help in that effort.

When I presented some initial strategies to the management team, someone cautioned me about something called “mass mailing” restrictions. I had proposed a series of regular communications to our neighborhoods, personalized with messages from their respective elected officials. I can’t believe something as positive as neighborhood newsletters and questionnaires could somehow be unlawful. Can you enlighten me?

Answer

The Political Reform Act’s mass mailing prohibition is one of those laws that can sneak up you. Because of this, it’s worthwhile to make sure you have a firm grasp of when the prohibition does and does not kick in.

The threshold question to ask is whether a communication being produced by the agency involves mentioning or featuring an elected official. If so, a rather complex analysis is needed to determine whether the communication is OK.

What’s the Big Deal?

The mass mailing prohibition is part of the state’s Political Reform Act. One of the act’s key purposes was to eliminate practices that favor incumbent elected officials so that elections could be conducted more fairly.1 The mass mailing restriction helps accomplish that goal by prohibiting elected officials from using public funds to perpetuate themselves in office by keeping their name before the voters, as an appellate court noted in upholding it.2

Like many aspects of the Political Reform Act, the mass mailing prohibition comes directly from the voters. The present version of the restriction was adopted in June 1988. Furthermore, the restriction adopted by the voters is quite broad, though deceptively short: “[N]o newsletter or other mass mailing shall be sent at public expense.”3

Prior to the Political Reform Act, the ability to do politically useful mass mailings at public expense was considered a perk of public office that provided incumbents an unfair advantage. Thus, the mass mailing restrictions involve the ethical values of fairnessand responsibility(all public servants have a responsibility to not misuse public resources for personal gain).

Key Questions to Ask to Determine Whether the Prohibition Applies

So what constitutes a mass mailing? The Political Reform Act states:

“Mass mailing” means over 200 substantially similar pieces of mail, but does not include … mail that is sent in response to an unsolicited request …4

The Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC) has adopted regulations to further explain what the mass mailing prohibition covers.5

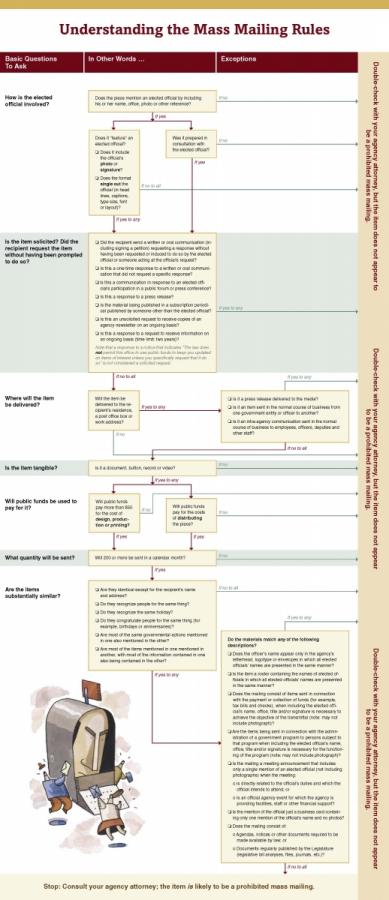

These regulations may appear extraordinarily complex. This is in part because of individuals who try to circumvent the restrictions (which then creates a need to specify certain practices that violate the restriction) as well as the fact that there are a number of perfectly appropriate kinds of governmental mass mailings. In an effort to make these regulations easy to understand and follow, please see the flow chart.

Basically, the analysis involves asking eight questions:

- How is any elected official involved in the informational piece you are preparing?

- Is the item solicited and, if it is, did the recipient request the item without having been prompted to do so?

- Where will the piece be delivered?

- Is the piece tangible; is it a document, button, record or video?

- Will public funds be spent to either produce or distribute the piece?

- How many will be sent?

- Is there a substantial similarity among items being sent?

- Does the piece fall within any of the exceptions to the mass mailing prohibition?

Questions 1, 2 and 5 relate to the heart of the prohibition’s purpose — to prevent incumbents from using public funds to boost their visibility with voters by sending them unsolicited information. The regulations say that public funds cannot pay for the distribution of the mailing (presumably postage).6 Nor may public funds pay for the costs of design, production or printing of the mailing, if those costs exceed $50.7

Questions 3 and 4 address the issue of whether the piece in question is in fact a mailing. Note that the mass mailing prohibitions do not apply to Internet-related communications,8 although the prohibitions against personal or political use of public resources imposes limitations on what can be presented on a public agency website.9

Questions 6 and 7 probe the issue of whether something is a mass mailing, defined as more than 200 substantially similar items in a single calendar month.10 Note that minor changes in the document may not be enough to take a mailing out of the category of a prohibited mass mailing.11

Finally, question 8 reflects the fact that there are some kinds of mailings that government must send in order to function. The FPPC’s regulations recognize this fact by creating a series of exceptions to the flat ban against mass mailings.12

For example, if your community outreach strategy involves a series of community meetings, there is an exception to the mass mailing prohibition for meeting announcements when:

- The meeting is directly related to the elected officer’s existing governmental duties;

- The elected officer is holding the meeting; and

- The elected officer intends to attend the meeting13

In addition, the meeting announcement may generally only include a single mention of the officer’s name; it may not include the officer’s photo or signature.14 So when a council member wanted to send out an invitation to a breakfast roundtable at public expense that included a photograph along with two mentions of the council member’s name, the FPPC said the invitation had to be changed to eliminate the photograph and one of the references to his name to qualify for this exception.15

Things to Watch Out For

Although it seems relatively straightforward, the mass mailing prohibition can take you by surprise. For example, watch out for mailings sent by other organizations that receive public funding from your agency.

The FPPC has ruled that the mass mailing prohibition means a city council member’s business could not run an ad in a chamber of commerce newsletter. The city council member was an accountant, whose firm name included his last name (as well as two others). The problem was that the chamber of commerce was partially funded with city funds, and the ad would have included the firm name as well as a picture of all 12 members of the firm.16

The FPPC has been consistent in its view that the fact an elected official is paying for an ad in a mailing doesn’t matter. For example, the FPPC also nixed a paid ad by a council member’s business in a city newsletter when the business and Web address for the business included the council member’s last name.17 This is in part because these ads are paid for in consultation with the city council member, so any inclusion of the council member’s name, office, photograph or other reference is enough to trigger the prohibition.18

In light of this, it’s wise to review the prohibitions with elected officials whose businesses or nonprofits may run paid ads in newsletters that are be funded in whole or part with local agency funds. If the newsletter mentions the official’s name (for example, if the official’s name is part of the business) or photo, there may be a problem.

Penalties for Violating the Prohibition

These restrictions are part of the Political Reform Act, which means civil and criminal sanctions apply (misdemeanor for knowing or willful violations,19 fines of up to $5,000 per violation,20 and possible reimbursement for the costs of any litigation initiated by private individuals, including reasonable attorneys’ fees21). Other consequences include the embarrassment to the agency for having violated restrictions on the proper use of public resources and, of course, the costs of defending yourself in any action brought to enforce the prohibition (see the December 2005 issue of Western City for a further analysis of these costs).

The Law as a Floor for Ethical Conduct

The regulations are tightly written to minimize the opportunity for mischief. Undoubtedly there are clever individuals who can find a way around the restrictions and construct a mailing that falls outside the prohibition. However, as already mentioned, there are also general prohibitions against the use of public resources for political purposes.

Even if a particular course of action may comply with the letter of the law, public officials should keep in mind that the law is a floor for ethical conduct, not a ceiling. Just because a mailing might be legal doesn’t mean it would be ethical if it violates the spirit and purposes of the mass mailing prohibitions.

Footnotes

[1] Cal. Gov’t Code § 81002(e).

[2] See Watson v. California Fair Political Practices Commission, 217 Cal. App. 3d 1059, 1074, 266 Cal. Rptr. 408, 416-7 (2d Dist. 1990), rev. denied 1990.

[3] Cal. Gov’t Code § 89001.

[4] Cal. Gov’t Code § 82041.5.

[5] See 2 Cal. Code Regs. § 18901.

[6] 2 Cal. Code Regs. §18901(a)(3)(A).

[7] 2 Cal. Code Regs. §18901(a)(3)(B).

[8] See, e.g., FPPC Advice Letter No. A-04-130 (July 13, 2004) (approving the inclusion of a mayor’s welcome message on the city website).

[9] See Cal. Gov’t Code § 8314; Cal. Penal Code § 424.

[10] See 2 Cal. Code Regs. § 18901(a)(4).

[11] See 2 Cal. Code Regs. § 18901(c)(3) (definition of “substantially similar”).

[12] See generally 2 Cal. Code Regs. § 18901(b). The FPPC’s authority to create these exceptions was recognized in Watson v. California Fair Political Practices Commission, 217 Cal. App. 3d 1059, 266 Cal. Rptr. 408 (2d Dist. 1990), rev. denied 1990.

[13] See 2 Cal. Code Regs. § 18901(b)(9)(A).

[14] See 2 Cal. Code Regs. § 18901(b)(9)(B).

[15] See FPPC Advice Letter No. A-04-004 (Jan. 27, 2004).

[16] See FPPC Advice Letter No. A-04-026 (April 26, 2004).

[17] See FPPC Informal Advice Letter No. I-05-183 (Sept. 8, 2005).

[18] Id.

[19] See Cal. Gov’t Code § 91000(a).

[20] Cal. Gov’t Code § 83116.

[21] Cal. Gov’t Code § 91012.

This article appears in the February 2006 issue of Western

City

Did you like what you read here? Subscribe

to Western City