How communities can enhance their viral wildfire immunity

Ed Fleming is the emergency services coordinator at the La Palma Police Department and retired division chief for the Orange County Fire Authority. He can be reached at EFleming@CityofLaPalma.org. Illustrations by Katherine Baeten, a freelance artist and art educator in Door County, Wisconsin.

The pandemic gave us a fundamental understanding of how a virus can spread. The most destructive virus outbreaks can start small, perhaps a few hundred or a few thousand cases. But then cases begin to increase exponentially — doubling, tripling, in size over a few days as it leaps over our defenses.

In many ways, wildfires spread just like viruses, but faster. So, what can epidemiology teach us about making our communities safer against wildfires? It is a question worth investigating given our current fire conditions. The ten most destructive wildfires in California history have occurred since 1991.

These megafires have occurred as many communities have pushed deeper into California’s wildland-urban interface — regions where the wilderness meets or intermingles with the built environment. This is driven in part by a public passion for suburban and rural living, but also by California’s housing shortage. According to the U.S. Forest Service, the wildland-urban interface area is the “fastest growing land use type in the conterminous United States.”

Simultaneously, droughts, tree mortality, bark beetle infestations, a changing climate, and lightning outbreaks have helped create tinderbox conditions. California’s most destructive wildfires occur during the autumn months when dry vegetation is exposed to strong northeasterly breezes, known locally as Santa Ana, Mono, and Diablo winds.

How does a wildfire behave like a virus?

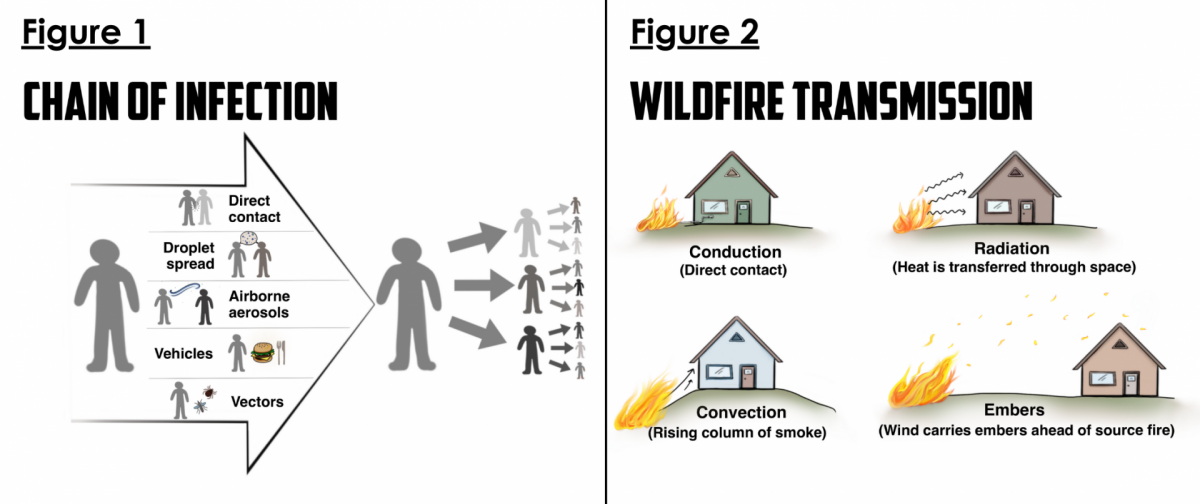

Viruses are transmitted through direct skin-to-skin contact; droplets, sneezing, or coughing; airborne aerosols; vehicles, such as food or water; and vectors, such as fleas, ticks, and mosquitoes. Airborne viruses can travel some distance before they infect a new unsuspecting host. As shown in Figure 1, a virus enters a susceptible host through portals such as skin, eyes, nose, mouth, and respiratory tract. Once the new host is infected, viruses multiply and spread to others, leading to a chain of infection.

As illustrated in Figure 2, a wildfire transmits heat much like a virus. Combustible objects accumulate heat by conduction through direct contact; radiation via infrared heat waves; convection through superheated smoke; and ember cast, where hot flying embers are blown ahead of the main fire.

Just like a virus, wildfires can spread quickly into nearby communities. Flying embers, burning twigs, and glowing firebrands are carried by the wind up to a mile ahead of the main fire, where they infect a new host, such as foliage or combustible structures. Dry vegetation, hot weather, and strong winds make contagious spread more likely.

Heat enters new host dwellings through combustible roofs, overhanging eaves, unprotected windows, and unshielded attic vent coverings. Once ignited, an interior attic fire may incubate before the symptoms become visible on the outside. At this stage, the attic fire has reached a destructive intensity and the host house is now capable of infecting other structures. As the chain reaction propagates, the wildfire may initially spread faster than first responders can react.

Moreover, much like a lit birthday candle held upside-down, wildfires burn most vigorously in the upslope direction. This means that fires may spread even faster on steep slopes or within wind-prone canyons.

Encourage home hardening

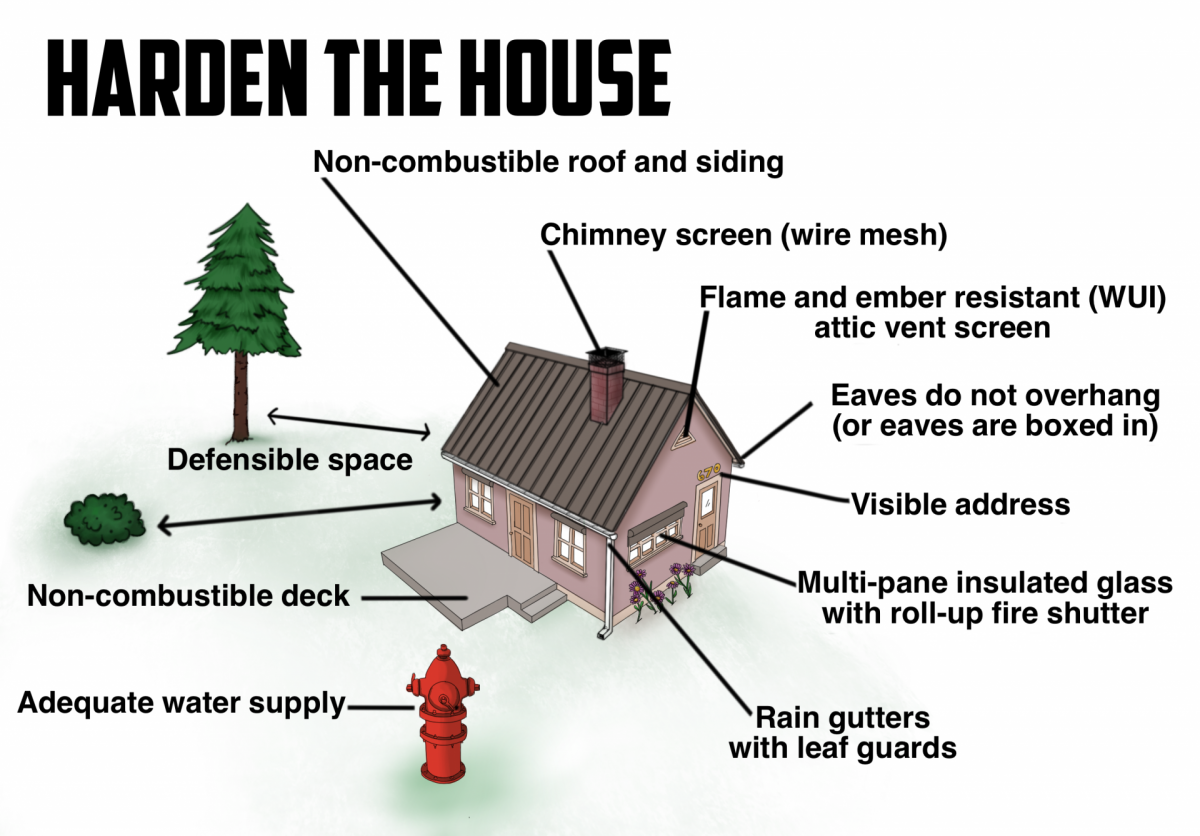

Thanks to years of meticulous case studies, health officials have multiple tools to slow the spread of a virus, such as masks and physical distancing. Similarly, fire officials can slow the spread of wildfires by applying California Fire Code Chapter 49, which is designed to reduce ember intrusion and reduce losses to conflagrations.

Building officials can also require protection from intruding embers and other heat sources by adhering to California Building Code Chapter 7A, which applies to buildings within fire hazard severity zones and wildland-urban interface areas. The section requires things like vegetation management practices, defensible space, ignition-resistant construction materials, and fire-resistant exterior windows.

When a wildfire spreads, it is often very clear which buildings were protected by newer building and fire codes. The 2008 Freeway Complex Fire damaged or destroyed over 350 structures in several communities within Riverside, San Bernardino, and Orange counties. Notably, all the damaged or destroyed homes were constructed prior to 1996 and were thus not protected by local construction ordinances.

However, the homes in the northeastern community of Casino Ridge met the requirements of the 1996 ordinance and were undamaged by the fast-moving flames. Firefighters stated that they were able to focus resources and efforts on other areas of the city since the Casino Ridge neighborhood was developed to withstand a wildfire with little firefighting intervention.

Much like an epidemic, weathering a fire threat is a community effort. Collaboration between residents and local agencies plays a crucial role in slowing or preventing dangerous conflagrations. As a supplement to the fire and building codes, local agencies can support their local fire safe councils.

These community-led organizations help residents acquire the education, resources, and tools they need to better prepare themselves for wildfires. Local fire safe councils may be eligible for assistance through the California Fire Safe Council, which administers U.S. Forest Service State Fire Assistance grants and other funding opportunities.

Some fire safe councils participate in red flag patrols and other preparedness programs. The Laguna Beach Fire Safe Council even has a fire-safe demonstration garden, which shows how homeowners can plant native vegetation in a defensible, aesthetically pleasing, manner.

Capitalize on existing resources to increase community awareness

One of the major lessons of the pandemic is the importance of clear, scientifically sound community education. When residents can preemptively remove themselves from danger, emergency responders can focus on the areas of greatest need. Local governments do not need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to community education and wildfires.

CAL FIRE’s Ready for Wildfire web app and the Ready-Set-Go program can help residents maintain defensible space and harden their homes against wildfire. The app also provides information about nearby active wildfires. The Ready-Set-Go checklist includes several helpful evacuation tips about go-bags, pre-planned travel routes, and what to do if you cannot evacuate.

Residents can also view their county’s Fire Hazard Severity Zone map and sign up for fire weather watches and red flag warnings through the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration weather radio network.

Additionally, city officials can encourage residents to adopt fixtures like exterior window shutters and automatic exterior sprinkler systems. If warning times are sufficient, residents can also deploy exterior window coverings and apply fire-retardant gel to their homes before they evacuate. Some fire-retardant gel coatings can last up to 24 hours.

These resources, combined with evacuation exercises and public alert and warning systems, can buy precious time for fire crews and residents.

Be aware of your terrain

Equally important for cities is the type of terrain they are building in. The type of land in the wildland-urban interface can vary greatly. City and county officials — in cooperation with planning commissions, fire-safe councils, professional foresters, and insurance companies — should consider wildfire-prone topography and wildfire risk when developing rural residential districts.

Local agencies should also require emergency evacuation routes out of neighborhoods while providing ingress for firefighting, law enforcement, and animal control agencies. Some communities require 28-foot-wide roadways in high fire hazard areas, as well as a minimum of two ways into all communities with 150 or more homes. Much like a mask or physical distancing, these methods can slow the spread of wildfires and give residents more time to evacuate.

Wildfire prevention is a community effort

California’s suburban expansion into rural districts is placing greater demands on overstretched emergency services. Just as viruses are easily transmitted in cold weather and crowded spaces, wildfires are easily transmitted in dry weather, on steep slopes, and in dead vegetation. Homes in these areas require extra levels of protection. By understanding the modes of wildfire transmission, local governments and residents can better protect against viral wildfires by investing in community education, hardened homes, and each other.