A Primer on California City Revenues, Part One: Revenue Basics

Michael Coleman is principal fiscal policy advisor to the League and can be reached at coleman@muniwest.com. More information on city finance is available at www.californiacityfinance.com. Coleman comments on local government finance topics on Twitter (@MuniAlmanac) and Facebook (www.facebook.com/MuniAlmanac).

You don’t have to scratch any local government issue very deeply to find the question of money: What’s this going to cost? What are we going to get for that price? Is this project worth it?

How does your city pay its bills? What does the future hold for city service costs and funding? Though every city is different — each with its own needs, local economy, expectations, protocols, responsibilities and finances — some essential elements of city revenues and spending are common to cities throughout California.

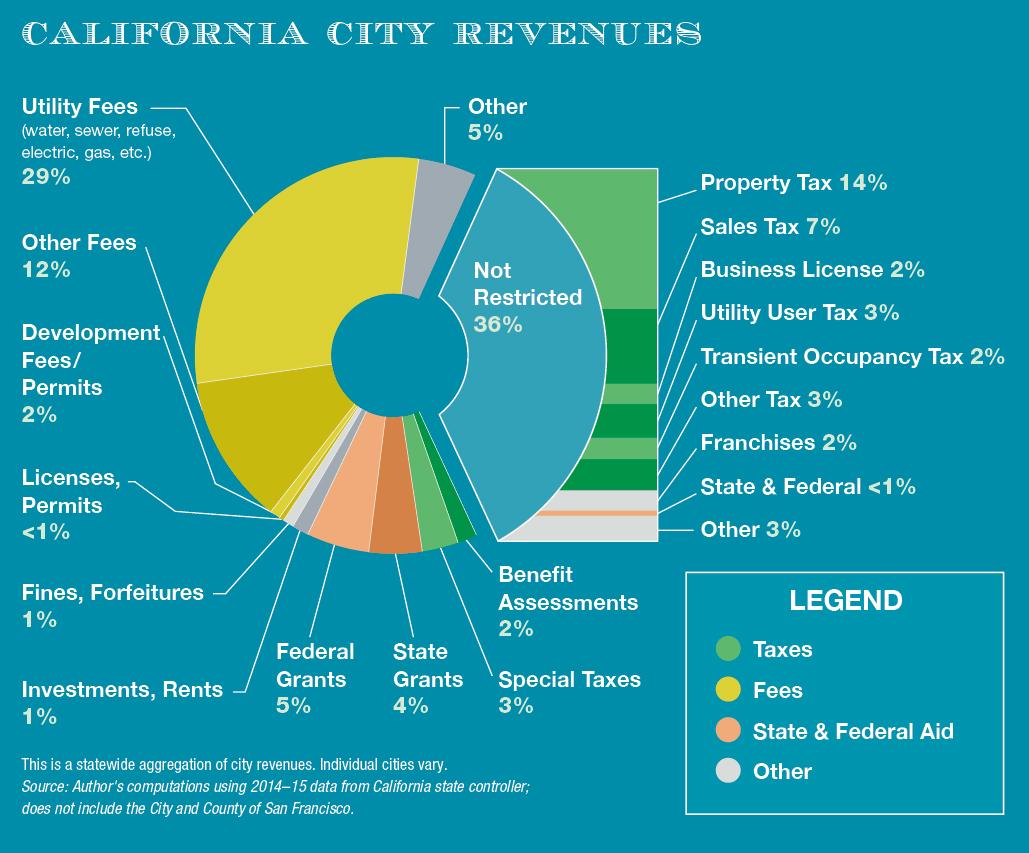

An Overview of City Revenue Sources

Revenue, the bread and butter of city budgets, comes from a variety of sources. Some revenue is restricted by law to certain uses; some revenue is payment from customers for a specific service. Other revenue requires voter approval for rate increases. Still other revenue comes from state and federal agencies, almost all of it with strings attached.

Taxes

A tax is a charge for public services and facilities. There need not be a direct relationship between the services and facilities used by an individual taxpayer and the tax paid. Cities may impose any tax not otherwise prohibited by state law (Gov’t. Code Section 37100.5). The state prohibits local governments from taxing certain items, including cigarettes, alcohol and personal income; the state taxes these for its own purposes.

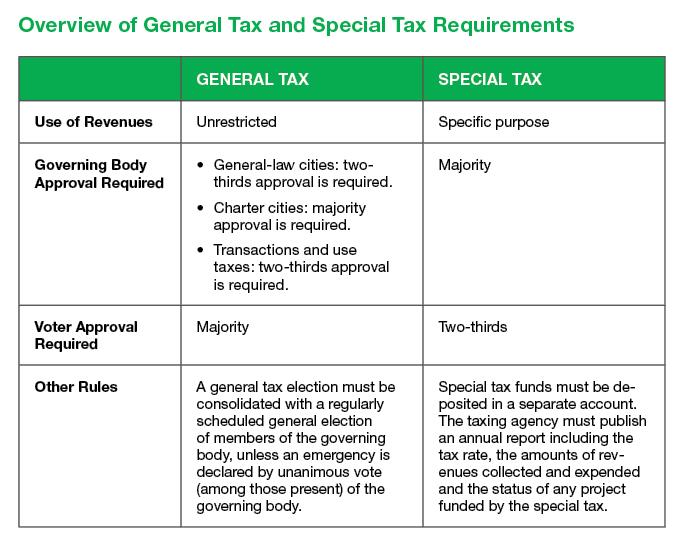

The California Constitution distinguishes between a general tax and a special tax. General tax revenues may be used for any purpose. A majority of voters must approve a new general tax, its increase or extension in the same election in which city council members are elected. Special tax revenues must be used for a specific purpose, and two-thirds of voters must approve a new special tax, its increase or extension.

Fees, Charges and Assessments

A fee is a charge imposed on an individual for a service that the person chooses to receive. A fee may not exceed the estimated reasonable cost of providing the particular service or product for which the fee is charged, plus overhead. Examples of city fees include water service, sewer service connection, building permits, recreational classes and development impact fees.

Cities have the general authority to impose fees (as charges and rates) under the cities’ police powers granted by the state Constitution (Article XI, Sections 7 and 9).

State law sets specific procedures for fee and rate adoption. Proposition 218 provides special rules for property-related fees used to fund property-related services.

Special benefit assessments are charges levied to pay for public improvements or services within a predetermined district or area, according to the benefit the parcel receives from the improvement or services. The state Constitution requires property-owner approval to impose a benefit assessment. Other locally raised revenues include licenses and permits; franchises and rents; royalties and concessions, fines, forfeitures and penalties; and investment earnings.

Intergovernmental Revenue

Cities also receive revenue from other government agencies, principally the state and federal governments. These revenues include general or categorical support monies called subventions, as well as grants for specific projects and reimbursements for the costs of some state mandates. Intergovernmental revenues provide 10 percent of city revenues statewide.

Other City Revenues

Other sources of revenue to cities include rents, franchises, concessions and royalties; investment earnings; revenue from the sale of property; proceeds from debt financing; revenues from licenses and permits; and fines and penalties. Each type of revenue has legal limitations on what may be charged and collected as well as how the money may be spent.

Putting Money in its Proper Place

The law restricts many types of city revenues to certain uses. As explained earlier, a special tax is levied for a specific program. Some subventions are designated by law for specific activities. Fees are charged for specific services, and fee revenue may fund only those services and related expenses. To comply with these laws and standards, finance departments segregate revenues and expenditures into separate accounts or funds. The three most important types of city funds are special revenue funds, enterprise funds and the General Fund.

Special revenue funds are used to account for activities paid for by taxes or other designated revenue sources that have specific limitations on use according to law. For example, the state levies gasoline taxes and allocates some of these funds to cities and counties. A local government deposits gasoline tax revenue in a special fund and spends the money for streets and road-related programs, according to law.

Enterprise funds are used to account for self-supporting activities that provide services on a user-charge basis. For example, many cities provide water treatment and distribution services to their residents. Users of these services pay utility fees, which the city deposits in a water enterprise fund. Expenditures for water services are charged to this fund.

The General Fund is used to account for money that is not required legally or by sound financial management to be accounted for in another fund. Major sources of city General Fund revenue include sales and use tax, property tax and locally adopted business license tax, hotel tax and utility user taxes.

Local Tax and Revenue Limitations: Proposition 13 and Its Siblings

Local officials have limited choices in governing, managing their finances and raising revenues to provide services needed by their communities. Voters have placed restrictions as well as protections in the state Constitution. The Legislature has acted in various ways both to support and provide and to limit and withdraw financial powers and resources from cities, counties and special districts.

Significant limitations on local revenue-raising include:

- Property taxes may not be increased except with a two-thirds vote to fund a general obligation bond (most local school bonds can now be passed with 55 percent voter approval);

- The Legislature controls the allocation of local property tax among the county, cities, special districts and school districts within each county;

- Voter approval is required to enact, increase or extend any type of local tax;

- Assessments to pay for public facilities that benefit real property require property-owner approval;

- Fees for services and the use of local agency facilities may not exceed the reasonable cost of providing those services and facilities; and

- Fees for services such as water, sewer and trash collection are subject to property-owner majority protest.

Local Revenue Protections

The Legislature has enacted many complicated changes in state and local revenues over the past 30 years, which at times have had significant negative fiscal impacts on city budgets. In response, local governments and their allies drafted — and voters approved — state constitutional protections limiting many of these actions. At times, these protections have resulted in the Legislature undertaking even more complex maneuvers in efforts to solve the financial problems and protect the interests of the state budget.

In response to actions of the Legislature and the deterioration of local control of fiscal matters, local governments placed on the ballot and voters approved Proposition 1A in 2004 and Prop. 22 in 2010. Together, these measures prohibit the state from:

- Enacting most local government mandates without fully funding the costs (the definition of a state mandate includes the transfer of responsibility for a program for which the state was previously fully or partially responsible);

- Reducing the local portion of the sales and use tax rate or altering its method of allocation, except to comply with federal law or an interstate compact;

- Reducing the combined share of property tax revenues going to the cities, county and special districts in any county; and

- Borrowing, delaying or taking motor vehicle fuel tax allocations, gasoline sales tax allocations or public transportation account funds.

Coming Next Month in Western City

Part Two of “A Primer on California City Revenues” will address major city revenues.

Related Resources

California Local Government Finance Almanac, www.californiacityfinance.com

Financial Management for Elected Officials, Institute for Local Government, www.ca-ilg.org/financialmanagement

Public Engagement in Budgeting, Institute for Local Government, www.ca-ilg.org/PEbudgeting

The California Municipal Revenue Sources Handbook, League of California Cities, www.cacities.org/Resources/Publications

Guide to Local Government Finance in California by Multari, Coleman, Hampian and Statler, Solano Press

A Public Official’s Guide to Financial Literacy

Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) www.gfoa.org/

This article appears in the November 2016 issue of Western

City

Did you like what you read here? Subscribe

to Western City