Reassembling Redevelopment

Dan Carrigg is deputy executive director and legislative director for the League and can be reached at dcarrigg@cacities.org.

In recent months, gubernatorial candidates and legislators have been discussing the need to bring back redevelopment, which some have called “redevelopment 2.0.” These conversations are positive for the future of California cities, given the importance of this former tool in revitalizing urban cores, supporting economic development and building affordable housing. Yet several new tax-increment tools have already been created, further complicating the policy discussion. Should new tools be added to the existing ones or is this about reviving old redevelopment law?

The new tax-increment tools lack the concentrated financial impact provided by the former redevelopment tool. Left unaddressed, this financing gap presents major challenges for the future use of these tools.

The State of California should also be concerned, because weak local financing options will diminish many policies that it seeks to advance. The state is investing billions of dollars to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and vehicle miles traveled, increase transit usage, improve water infrastructure, build affordable housing and assist disadvantaged communities. The location of future development is critical to the success of these policies. Without sufficient local financing resources, however, many local projects will fail to maximize opportunities.

To prepare for the coming policy discussions, it’s helpful for cities to:

- Revisit the benefits and challenges of the former redevelopment tool and how its elimination affected cities;

- Summarize the League’s work since 2012 in shaping new tax-increment tools;

- Compare prior redevelopment financing with new tools;

- Review current state policy priorities to identify common ground; and

- Outline what would be most helpful for cities going forward.

Redevelopment’s Benefits

For over 60 years, redevelopment was the most robust community revitalization and economic development tool that cities had. Its use blossomed because it offered the opportunity to concentrate significant financial investment for reinvigorating an area without triggering a tax increase.

Cities used redevelopment to:

- Clean up brownfields;

- Restore and upgrade infrastructure;

- Assemble smaller and odd-shaped parcels;

- Improve local parks, libraries and other civic amenities;

- Assist local businesses;

- Expand economic development; and

- Build transit-oriented development and affordable housing.

When redevelopment was eliminated in 2011, nearly 400 redevelopment agencies were operating, generating over $6 billion in annual revenue and providing the state’s largest source of funding for affordable housing at over $1 billion per year.

At a post-dissolution legislative hearing, former longtime Pasadena Mayor and then-League President Bill Bogaard described how the City of Pasadena used the tool to turn around its downtown, including bringing back businesses, renovating buildings and adding higher density affordable housing. He noted that redevelopment gave a community the resources to solve problems — identified by residents — that developers wouldn’t address, and this was one of its greatest benefits. Resolving these problems helped build community support for major revitalization efforts. Without redevelopment, such resources no longer exist.

Redevelopment’s Challenges

Redevelopment was a powerful tool, but — like any large enterprise — imperfect. With agencies operating independently with broad powers and millions of dollars in revenue, there were bound to be critics and problems. Residents vigorously debated the changes that revitalization can bring, including increased traffic and noise and the fear of being displaced. Projects can be poorly conceived, and governing boards can lose touch. Redevelopment’s problems surfaced in lawsuits and unfavorable media coverage.

But when problems occurred, corrections were made under robust legislative and administrative oversight. Redevelopment’s financial data was sent to the state controller, and housing obligations were tracked in meticulous detail. The Legislature constantly refined the laws, and the creation, powers, administration and use of redevelopment were prescribed in over 200 pages of statute.

How Ending Redevelopment Affected Cities

The elimination of redevelopment has had many lasting impacts as decades of community revitalization plans were wiped out. Shutting down this long-standing tool was bound to be controversial, and the disputes were compounded by:

- The lack of an established dissolution regulatory structure with consistent rules;

- Two comprehensive budget trailer bills in 2012 and 2015 that revised and reinterpreted dissolution laws largely to the benefit of the state’s coffers;

- No state policy guidance or priorities on which projects — affordable housing, transit-oriented development, etc. — should be salvaged; and

- Weak legislative oversight.

This situation left the courts and staff at the state Department of Finance (DOF) acting as the final arbiters of many decisions related to redevelopment’s dissolution.

During this period, cities also lost most of their experienced economic development staff. Those who remained focused on salvaging whatever was possible in the DOF-managed dissolution process with successor agencies and local oversight boards. In 2013, the state also eliminated enterprise zones, which had provided employers with tax incentives to attract jobs to state-approved zones with higher unemployment. This experience caused doubts about the reliability of the state’s sustained interest and commitment to community development.

Local budget conditions have also declined. Staffing levels have not rebounded since the severe staffing cuts made during the Great Recession. Sales tax is eroding as a reliable revenue source due to the changing retail marketplace, the challenges of collecting taxes from internet commerce and a continued shift toward a service economy. Property tax growth varies widely depending on local economic conditions. Public pension liabilities will double over the next seven years, outstripping revenue growth and further squeezing cities’ ability to provide essential services and invest in the future. Several ballot measures currently being circulated would, if approved by voters, further restrict local revenue.

Cities are resilient and will continue to push forward, but even with new tools, it will take decades to recover from the elimination of redevelopment.

Redevelopment Financing

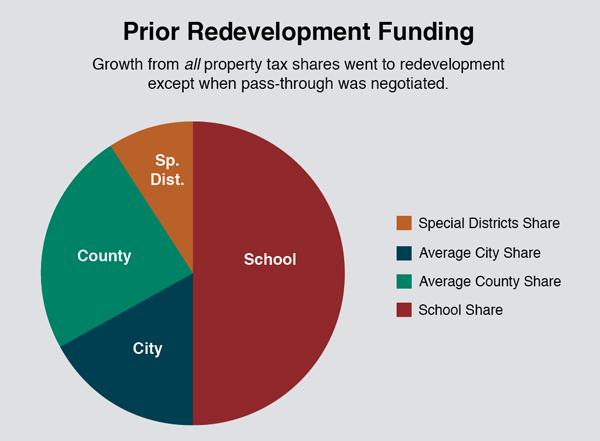

Redevelopment financing through tax increment was based on two principles:

- Improvements could be made to a deteriorated area and the increased property values would pay for the improvements; and

- Improving a deteriorated area increased property tax revenue for all taxing entities.

- Under redevelopment, the property tax base was frozen within a designated project area. Other taxing entities (counties, schools and special districts) would continue to receive the amounts they received during the base year when the project was established plus 2 percent annual growth. In some cases, property tax pass-through agreements were negotiated to allow some tax growth to flow to a specific entity.

After a plan was adopted, however, and as improvements were made, all property tax growth “increment” was dedicated to the project and repayment of debt. This was the heart of redevelopment financing and the core of the debate that led to its demise. Counties and special districts disliked not being part of the decision to form redevelopment agencies in cities and had other funding priorities; state budget drafters complained because Proposition 98 (1988) required the state to backfill schools’ losses from redevelopment diversion that by 2011 amounted to about $2 billion per year.

New Tax-Increment Tools Lack Financial Capacity

Compared with previous redevelopment, the new tools have limited financial capacity, thus requiring innovative thinking and new partnerships to maximize their potential. The new tools are:

- Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs);

- Community Revitalization and Investment Authority (CRIA);

- Affordable Housing Authorities (AHAs);

- Annexation Development Plans (ADPs);

- Seaport Infrastructure Financing Districts (SIPDs); and

- Infrastructure and Revitalization Financing Districts for former Military Bases (IRFDs).

Under the old model, after a city formed a redevelopment agency, all future growth from property tax shares — not just the city’s share — was directed to the redevelopment agency. This policy also reflected the philosophy that redevelopment created jobs and economic activity and increased property values, allowing all stakeholders to benefit.

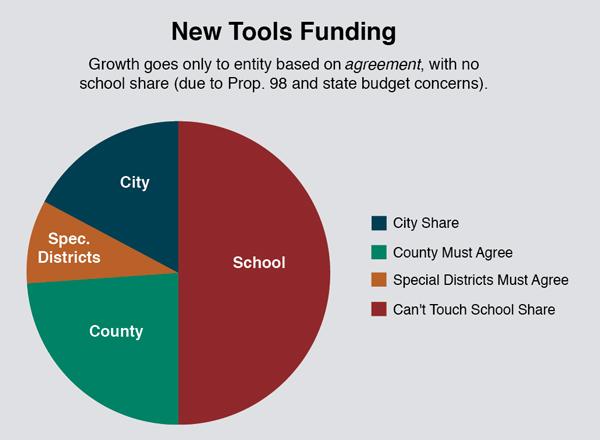

With the new tools, however, tax increment is much different: Agreement by any affected agency is now required — and schools are not currently allowed to participate. Cities, counties and special districts can choose whether to participate in a tax-increment financing project. A newly formed agency is entitled only to the increment generated on its own share of the property tax unless other local agencies also agree to contribute their shares. For example, a city can direct only the increment derived from its own share to this purpose, unless the county and/or special districts also agree to have the growth of their respective shares dedicated. As a result, local governments must collaborate on infrastructure and economic development in order to maximize the tool’s financial capacity.

When these tools were created, the Brown administration insisted on prohibiting access to growth from the school share of property tax. This is a major reduction in financial capacity because approximately 50 percent of property taxes are allocated to schools. Such restrictions, however, can be removed or allowed under specific conditions by future legislation. Schools are protected from negative impacts of tax-increment financing by Prop. 98, which requires the state to backfill any losses.

So far, however, examples of collaborative efforts with cities, counties and special districts are hard to find. One reason is these tools just took effect within the past several years. Many city officials have been bogged down by redevelopment dissolution, leaving little time to evaluate or consider new tools. It also takes time to properly assess these options and conduct conversations with other taxing entities to explore possible shared priorities. And at some point, the numbers don’t work. For cities, which receive just 5, 10 or 15 percent of the property tax share, there may not be enough financial benefit to justify using the tool.

Counties and special districts have also been cautious when approached by cities to explore interest in these new tools. County staff may have no prior experience with such financing methods or may have negative perceptions of former redevelopment. Their agency may be facing its own budget limitations and may have other challenges and priorities. Thus far, the potential for collaborative efforts with counties and special districts appears to be greater for infrastructure projects where there is a tangible benefit to unincorporated or special district territory.

And these tools — as currently constructed — appear less useful for traditional urban core redevelopment. Counties and special districts seem less interested in such projects. Given this lack of interest, the only other potential partner for a city would be the state — by authorizing investment of the school share of the property tax.

In addition to the traditional growth from property tax increment, entities that participate in an EIFD, CRIA or AHA can also agree to direct revenue from some or all of the following financing sources to the use of these tools:

- Property tax revenue that cities and counties receive in lieu of the former vehicle license fee (VLF);

- Property tax residuals that cities, counties and special districts may receive as the former redevelopment agencies, debts are repaid; and

- Funding derived from various special assessments and other financing mechanisms (such as landscaping and lighting districts, Mello-Roos taxes, etc.), which may be coordinated with these tools.

What Cities Need Going Forward: State Collaboration on Shared Priorities

As legislators and gubernatorial candidates explore options for restoring redevelopment tools, they will encounter numerous policy issues involving scope, financing and powers. They will also need to reconcile this discussion with the tax-increment tools created in recent years, which rely on collaboration among agencies rather than compulsion.

The biggest challenge of using these new tools is their insufficient financial boost, which is caused by prohibiting access to the school share of property tax. Because school financing connects to the state’s school funding obligations under Prop. 98, it is unlikely that the Legislature would authorize school districts to engage in such financing methods absent establishing a process that includes approval from a state entity.

Under these circumstances, what would be most helpful to cities? The state should identify its policy priorities and then offer to engage in collaborative tax-increment financing efforts with local agencies to accomplish mutual objectives. Examples of the state priorities that match existing local priorities include:

- Increasing affordable housing;

- Renovating urban core areas;

- Improving disadvantaged communities;

- Increasing transit-oriented development;

- Reducing carbon emissions;

- Maintaining critical infrastructure;

- Supporting economic development and job creation; and

- Improving local schools as part of community revitalization efforts.

The state should also develop a process for selecting projects, which could include review and approval by a state body such as the Strategic Growth Council, Infrastructure Bank or similar entity. Caps on annual allocations of the school share of tax increment could be established, but any previously committed tax increment must be guaranteed through project completion.

These new tools have potential but need a broader financing scope. If the state is willing to restore its prior contribution to tax-increment financing via the school share, then promising opportunities will emerge for state and local governments using a collaborative approach to tax-increment financing that advances shared priorities.

League Efforts to Develop New Tax-Increment Financing Tools: A Brief Overview

When redevelopment was eliminated, developing new tools that cities could use for infrastructure and economic development became a top League priority. The League formed the Task Force on the Next Generation of Economic Development Tools in spring 2012, chaired by then-League President Bill Bogaard. City officials on the task force provided key direction for the League to work on giving cities more options going forward. For the past six years, the League has focused on creating these options.

The League’s initial effort concentrated on making Infrastructure Financing District (IFD) law a useful tool. IFD law had many problems. It had been in place for 22 years and was rarely used. A major impediment was the requirement for two separate two-thirds public votes: one to establish a district, the other to issue debt. These vote requirements were sufficient to deter most agencies from considering further action. The League’s attorneys determined that these statutory vote requirements were not constitutionally required and identified other proposed changes to the law. Working in partnership with the California Building Industry Association, the League supported a series of amendments to SB 214 (Wolk), which passed in the Legislature. Regrettably, Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed this measure along with several others, including SB 1156 (Steinberg), which would have reauthorized redevelopment in a more limited form. The governor’s veto messages stressed his desire to keep cities focused on dissolving redevelopment.

In 2014, the League’s work on SB 214 resurfaced as part of a tool called the Enhanced Infrastructure Finance District (EIFD) proposed by the Brown administration. Rather than amending IFD law, as SB 214 had proposed, the administration opted to craft an entirely new statute that mirrored many IFD elements. In the ensuing negotiations, the League succeeded in eliminating a requirement to have a public vote prior to establishing a district. Though a 55 percent voter approval requirement to issue bonds remains in the law, other ways to secure financing have been identified. SB 628 (Beall, Chapter 785, Statutes of 2014) enacted EIFD law and the League sponsored a cleanup bill to EIFD law in 2015 — AB 313 (Atkins, Chapter 320, Statutes of 2015).

In addition, the League sponsored legislation to bring back the

tools and powers of redevelopment through a three-year

partnership with Assembly Member Luis Alejo (D-Watsonville) to

craft the Community Revitaliza-tion Investment Authority (CRIA)

law. The first effort, AB 1080 (Alejo) in 2013, stalled in the

Appropriations Committee after the administration made it clear

that no new economic development legislation would be signed that

year. The following year, Gov. Brown vetoed AB 2280 (Alejo), with

a veto message that sought drafting changes. In 2015, Gov. Brown

signed AB 2 (Alejo and

E. Garcia, Chapter 319, Statutes of 2015) into law. And in 2016,

the League sponsored a cleanup bill, AB 2492 (Alejo, Chapter 524,

Statutes of 2016).

Keeping in mind the “give us options” direction from its Task Force on the Next Generation of Economic Development Tools, the League also took advantage of growing legislative and administration interest in addressing the challenges faced by disadvantaged unincorporated communities. The League drafted and sponsored amendments to SB 614 (Wolk) to craft a simple tax-increment financing tool that cities and counties could use — as part of a city annexation of a disadvantaged unincorporated community — to repair and upgrade infrastructure. Gov. Brown signed it into law (Chapter 784, Statutes of 2014).

In 2017, the League drafted and sponsored SB 711 (Hill), designed

to authorize the use of the school share of property taxes to be

invested as part of local tax-increment financing projects using

EIFD, CRIA or other tools — if approved through a process using

the state’s Strategic Growth Council — for projects that would

advance important state goals, such as reducing greenhouse gas

emissions and vehicle miles traveled and supporting affordable

housing production and transit-oriented development. The bill

included requirements for program oversight, reporting, and

criteria and caps for the state’s financial exposure. Although

that effort did not gain momentum, it is likely

that such a concept will be revisited as discussions evolve about

a “redevelopment 2.0” mechanism.

The League and its attorneys also provided significant technical assistance in 2017 with drafting AB 1598 (Mullin, Chapter 764, Statutes of 2017), which used existing CRIA law as a model for adopting a new financing tool for affordable housing production.

As these new tools were developed, the League produced various white papers, hosted webinars, participated in workshops and collaborated with the California Association for Local Economic Development in the formation of a Tax-Increment Financing Technical Committee, which issued additional guides to the uses of these new tools (available at https://caled.org/tif-technical-committee).

In recent months, League representatives also met with gubernatorial candidates, legislators and their staff about how to restore and further enhance local community economic development tools. Several bills have been introduced in 2018, intended to refine discussions in anticipation that the next governor would be willing to approve a revised tool.

Summary of New Tax-Increment Tools

The Enhanced Infrastructure Financing District (EIFD) law (beginning with Section 53398.50 of the California Government Code) is the most popular tool so far. It provides broad authority for local agencies to use tax increment to finance a wide variety of public infrastructure. Private projects can also be financed, including affordable housing, mixed-use development and sustainable development, industrial structures, and facilities to house consumer goods and services. No public vote is required to establish an authority, and though a 55 percent vote is required to issue bonds, other financing alternatives exist.

Unlike former redevelopment, the EIFD imposes no geographic limitations on where it can be used and requires no blight findings. An EIFD can be used on a single street, in a neighborhood or throughout an entire city. It can also cross jurisdictional boundaries and involve multiple cities and a county. Though an individual city can form an EIFD without participation from other local governments, the flexibility of this tool and the enhanced financial capacity created by partnerships will likely generate creative discussions among local agencies on how the tool can be used to fund common priorities. Recent legislation, AB 1568 (Bloom, Chapter 562, Statutes of 2017), authorizes EIFDs to access sales tax in instances where the boundaries are “coterminous” with the boundaries of the underlying city or county and 20 percent of the revenue is spent on affordable housing on infill sites.

Community Revitalization and Investment Authorities (CRIAs) law (beginning with Section 62000 of the California Government Code) gives these authorities all the former powers of redevelopment agencies. A CRIA focuses on assisting with the revitalization of poorer neighborhoods and former military bases. While similar to redevelopment, a CRIA is more streamlined. Accountability measures are included to ensure that the use of the CRIA remains consistent with community priorities, and a 25 percent set-aside is included for affordable housing. Although an initial protest opportunity exists, no public vote is required to establish a CRIA, and bonds and other debt can be issued after a CRIA is established.

Affordable Housing Authority (AHA) financing law

(beginning with Section 62250 of the California Government Code)

is a new statute that authorizes a city or county to create by

resolution an affordable housing authority (coterminous with its

boundaries) with various powers and to dedicate a portion of its

property tax increment, sales tax and other revenues to develop

affordable (up to 120 percent of area median

income) housing.

An AHA may issue bonds; borrow; receive funds from and coordinate with other entities; remove hazardous substances; provide seismic retrofits; loan funds to owners and tenants to repair, improve or rehabilitate buildings in the plan area; and take other actions. The AHA has broad property acquisition and disposal authority. Creating an AHA or bond issuance does not require a public vote.

Annexation Development Plan (ADP) law (Section 99.3 of the California Revenue and Taxation Code) authorizes consenting local agencies (a city and/or a county or special district) to adopt tax-increment financing to improve or upgrade structures, roads, sewer or water facilities or other infrastructure as part of annexing a disadvantaged unincorporated community. An ADP can be implemented by a special district either formed for this purpose or incorporated into the duties of an existing special district. After the Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) approves the annexation, the special district can issue debt without an additional vote.

Seaport Financing Districts (SPDs) law (Section 1710, Harbors and Navigation Code of California) establishes a financing tool for seaport infrastructure based on a modified form of the EIFD law.

Infrastructure and Revitalization Financing Districts for Former Military Bases (IRFDs) law (beginning with Section 53369 of the California Government Code) creates infrastructure and revitalization financing districts separate and apart from existing law that established infrastructure financing districts (IFDs), authorizes a military base reuse authority to form a district and allows these districts to finance a broader range of projects and facilities.

Photo credits:Shotbydave (Man Pointing); Chaiyapruek2520 (Hats); DustyPixel (California Flag); Kanate (Construction Icons).