Rethinking budgeting: An idea whose time has come

Shayne Kavanagh is the senior manager of research and consulting for the Government Finance Officers Association. He can be reached at skavanagh@gfoa.org or (312) 578-2276.

Local governments have developed their budgets in essentially the same way for decades: Last year’s budget becomes next year’s budget with incremental changes at the margin. These budgets are built around line items — categories of spending like personnel, commodities, and contractual services — which are then grouped into departments and funds.

People have criticized this approach for almost as long as it has been in use with local governments.

The most prominent criticism is that past decisions are frozen in place past the point they are affordable or relevant. If a department gets a grant to increase staffing for a few years, those positions become part of the department’s baseline budget. Once the grant ends, the expenditure continues to be funded without evaluating whether those positions are creating sufficient value for the community. This “layering on” effect contributes to financial distress.

There are many other criticisms of the traditional budget, such as its lack of strategic focus and its tendency to promote conflicts among participants. These criticisms have led to attempts to do budgeting better, such as zero-base budgeting and priority-based budgeting.

“Governments have become accustomed to think a budget is like a routine set of exercises and that adding or changing a couple of exercises will fix fundamental weaknesses when transforming the entire routine is necessary,” San Dimas City Manager Chris Constantin said.

Among most local governments, the traditional budget has endured … and for good reasons. It is simple, the results are predictable, line items provide a sense of control, and incrementalism avoids radical change. However, there are new forces that make the traditional budget less tenable than in the past.

Ongoing threats are creating significant challenges to traditional budgets

There are several threats and opportunities that make the time ripe for rethinking the budget. Let’s review four.

The first threat is the stagnant or diminishing resources available to local governments. The traditional budget’s success rests on distributing budget increases to enough stakeholders to maintain a stable governing coalition. However, the traditional budget does not have a good answer to resource declines. This is why we see across-the-board cuts as a common response to fiscal distress: Everyone is cut evenly.

However, cutting everyone equally does not optimally size or shape government to the conditions it faces. Moreover, though federal money has made many local budgets flush in recent years, the long-term trajectory does not look nearly so good as aging demographics and slowing economic growth threaten to constrain revenues.

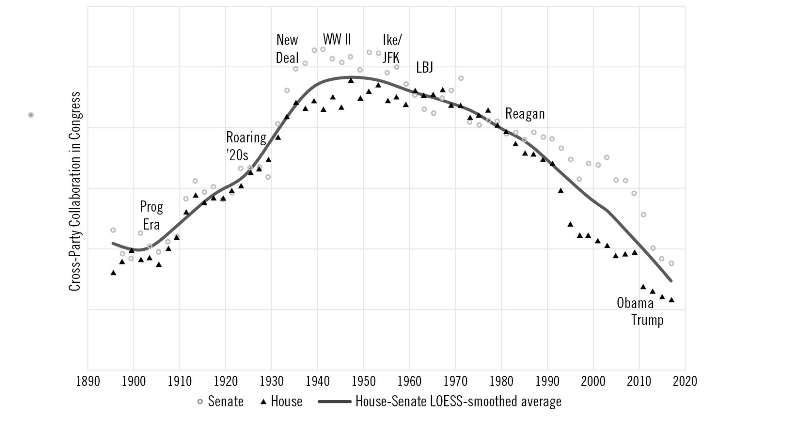

The second threat is the defining conflict of our times: political polarization. According to research by Robert D. Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett, cross-party collaboration in the U.S. Congress has reached all-time lows. Political conflict is not limited to federal government officials though. It affects the public, too. Conflict has gone along with declining trust.

The traditional budget lessens conflict by relying on historical precedent. However, when people no longer believe that others have their best interests in mind, they may not be willing to accept historical precedent as a justification for how resources are distributed.

Let’s move on to the opportunities.

Choice architecture and fairness

Modern behavioral science has new insights into how we make decisions. As a simple example, there is an underlying assumption in budgeting that people are rational — show them the numbers and they will make the right decision. However, behavioral science tells us that people are “predictably irrational.” They will interpret numbers and make choices in ways we might not expect.

Take a case that is an integral part of budgeting: choosing between options. From a purely rational standpoint, the more options you have, the better! But research shows that more options can work against good decision-making. This is called “choice overload” and is characterized by long delays in decision-making, not deciding at all, and frustration.

The most obvious solution is to present decision-makers with fewer choices. Decision-makers often appreciate a smaller number of solid choices that they can become familiar with rather than a wide range of options. Decision-makers still have a choice, but they don’t feel overwhelmed by too many choices.

That is, of course, but one approach for one common decision-making problem. The larger message is that the budget officer should be thought of as a “choice architect.” The way a choice is built influences how choices are made — like how the architecture of a physical space will influence how people use that space. Budget officers should be aware of how the presentation of information influences choice and use professional judgment to apply choice architecture wisely.

“Decision-makers rely on staff to understand their perspectives and to frame information and options for proper consideration while avoiding unnecessary confusion,” Constantin said.

It is also important to understand “fairness” and its implications for budgeting. Issues of fairness are often at the heart of the conflict. The conventional budget decreases or avoids conflict by relying on historical precedent, but many people no longer defer to historical precedent. Obtaining a more comprehensive understanding of “fairness — which is a multifaceted concept — can create solutions to some of the most important conflicts of our time. A limited understanding of fairness, at best, leaves opportunities unrealized and, at worst, risks more conflict with those that feel unfairly treated.

One major facet of fairness is a fair process. Ask yourself: Do people have the chance for input? Is the information used to make decisions seen as accurate? Are clear decision-making criteria applied equally to everyone? A fair process is critical because people are more willing to accept a decision that is not consistent with their self-interest if the process used to reach the decision was fair.

This has been shown in applications as disparate as courtrooms and corporate strategic planning and is no less valid in budgeting. There will never be enough resources for everyone to get everything they want. We have observed again and again that when budget processes are fair, they are far better at handling conflict. As a simple example, if there are clear criteria for deciding what gets funded and the people impacted by budget decisions have some input into those decisions, then people are far more likely to accept the decisions that come out of the process.

“It is rarely a good start if process fairness issues are raised and either not considered or ignored, to then hope for an outcome that would be accepted and/or devoid of challenge,” Constatin said.

Another crucial facet of fairness is how resources are distributed. Put simply, people get what they deserve. Of course, what people “deserve” is open to interpretation!

To illustrate, many local governments are grappling with “equity” in budgeting. “Equity” means people should be treated differently by public policy to compensate for different circumstances and consequently need help from government. It is often associated with equality of outcomes. However, this is not the only interpretation of what is “deserved.” “Proportionality” means people are given resources commensurate with their contributions. It is more closely associated with equality of opportunity.

Nearly everyone believes in a mix of proportionality and equity, but many people tend to give more weight to one or the other. This means budget officers will need to think about how and where the equity principle might be operative in budgeting and where the proportionality principle might hold sway.

This is not always an either/or proposition. There may be opportunities to satisfy both with clever approaches to public policy, such as segmented pricing of services. Segmented pricing is when different prices are offered to people to raise the chances of everyone buying, like when a salesperson offers a discount to a customer. Governments across the country already use segmented pricing when they give senior citizens discounts on property taxes.

When applied to government fines or fees, segmented pricing merely asks people to pay the price that they can afford — no more or less. It respects people’s differing ability to pay while also asking everyone to pay their fair share. There is also a good chance local governments will realize a net financial benefit as collection rates go up and collection costs are reduced. After all, when people cannot afford a fee or fine, they don’t pay it. The government then gets zero revenue and usually incurs additional collection costs. The individual also incurs debt and may have their credit record marred.

Rethinking budgeting in the city of San Dimas

San Dimas has been closely involved in the Government Finance Officers Association’s Rethinking Budgeting project, which focuses on many of the questions raised above. The city has applied “rethinking” to the problem of asset replacement. Many cities have large asset maintenance backlogs and San Dimas’ new approach echoes back to the forces of rethinking described earlier.

Resource allocation decisions can result in us-versus-them competition over limited resources. To solve this, San Dimas began planning how capital replacement would occur in assets that have a definable service life, such as HVAC systems. The city determined how much it needed to set aside for each asset and how much it needed to contribute annually to cover the future replacement or rehabilitation of the asset. The necessary resources were then set aside in a capital assets account.

This was a change from traditional budgeting. Previously, staff waited until something needed to be replaced. At that point, they had to consider its cost among all the other general operating requests, which meant departments were fighting for assets that needed to be replaced.

This new, forward-thinking method removes already incurred and necessary obligations from the annual competition for resources. By setting up this architecture for budget decisions, the city built trust in all departments that their annual requests would be on a level playing field and that allocation decisions would treat everyone fairly and not pit required obligations, such as an HVAC replacement, against other requests to increase funding.

This is just one of the changes the city has made or is working on that will result in better decisions in the budgeting process.

Putting resources where they matter most

These ideas and practices are just a few of those raised in the Rethinking Budgeting initiative. “The Government Finance Officers Association is trailblazing how local governments rethink budgets and challenging long-held perspectives on how we plan, develop, and implement our resource allocation practices,” said Constantin, a member of the project.

Local governments have both an imperative and an opportunity to rethink how they do budgeting. A budget is the most important policy to document because it decides how limited resources will be used to advance the public good. Doing so will help local governments achieve more than a balanced budget — it will also help achieve thriving communities for everyone by putting resources where they matter most.