Understanding the Role of Ethics Commissions

This column is a service of the Institute for Local Government (ILG) Ethics Project, which offers resources on public service ethics for local officials. For more information, visit www.ca-ilg.org/trust. ILG is grateful to these individuals for their assistance in preparing this article: Dan Purnell, executive director, Oakland Ethics Commission; Heather Mahood, assistant city attorney, Long Beach; Jennifer Sparacino, city manager, City of Santa Clara; and Carol McCarthy, deputy city manager, City of Santa Clara. Generous funding for the development of this column was provided by the International City-County Management Association (ICMA) Retirement Corporation (www.icmarc.org), whose mission is to build retirement security for the public sector.

Question

We have a citizens’ group in our community considering whether to propose establishing an ethics commission. We have looked for information about ethics commissions but have not really found much. Can you help?

Answer

There are a number of questions to ask in evaluating whether an ethics commission represents a useful tool for your community, including:

- What is your overall goal?

- What do you want an ethics commission to do?

- How would commission members be selected?

- What powers would the commission have?

- What resources are available to support the commission?

- What decision-making process should you use to determine whether a commission is right for the community?

Let’s look at each issue.

What Is Your Overall Goal?

The interest in creating an entity with some kind of responsibility for public service ethics can be inspired by any number of goals. One goal may be symbolic: to convey the message that ethics is important to a jurisdiction — so important that the jurisdiction has a body responsible for it. Unfortunately, symbolic gestures rarely accomplish much in terms of ethics.

Other goals may relate to the type of role the entity will play. An ethics task force can determine whether additional ethics measures and activities would be helpful in a jurisdiction. The City of Long Beach used this approach in 2001 when it created an ethics task force that came back a year later with a series of recommendations on how to enhance the ethical climate in the city. This kind of entity is an information-gathering and advisory body. However, the city council made the ultimate decision on whether to adopt the measures recommended by the task force.

One advantage of having an ethics task force is that it brings the community’s voice to the table about ethics in public service. Depending on the composition of the task force, the respect that task force members enjoy in the community can translate into community respect for the task force’s proposals.

Other communities have an ethics committee. The committee is a group of individuals that provides advice and feedback on how to promote and enhance the city’s ethics program. It can comprise members of the public, local officials or a combination of both. The City of Santa Clara’s ethics committee, for example, is composed of the mayor and two council members, the city manager, city attorney, city clerk, chief of police and the city’s ethics advisor. Other staff regularly attend. The meetings are open to the public, and the city posts meeting notices and mails them to those who wish to be notified.

An ethics commission is usually an in-dependent body that provides external oversight and enforcement of ethics laws. In California, the state’s Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC) performs this role for state and local officials subject to the Political Reform Act. The FPPC regulates:

- Campaign financing and spending at the state and local levels;

- Financial conflicts of interest at the state and local levels;

- Lobbyist registration and reporting at the state level;

- Post-governmental employment at the state and local levels;

- Mass mailings at public expense at the state and local levels; and

- Gifts and honoraria given to public officials and candidates at the state and local levels.

A key goal of an ethics commission is to enhance public trust in the ethics enforcement process by assigning it to a quasi-independent entity.

Local agencies can have ethics commissions that are charged with enforcing and taking other actions with respect to local ethics laws. Such commissions may also provide advice regarding local ethics laws as well as offer training on such laws.

One question to ponder is whether your city or county needs additional ethics regulations (see “There Ought to Be a Law”). California already has a fairly complex array of ethics laws. For an overview of existing state and federal ethics laws, see A Local Official’s Ethics Law Reference at www.ca-ilg.org/elr.

Common local ethics laws include laws that go beyond the minimum standards established in various state laws. These include laws that relate to campaign finance (contribution limits and public financing of campaigns), laws regulating lobbyists, open government or “sunshine” ordinances and more stringent gift rules.

What Do You Want an Ethics Commission to Do?

If creating an independent, regulatory entity would meet your community’s goal, the specific duties assigned to ethics commissions tend to fall into one or more of three categories:

- Overseeing and enforcing local ethics laws and/or codes;

- Providing advice to local officials on ethics and ethics laws; and

- Training local officials on ethics and ethics laws.

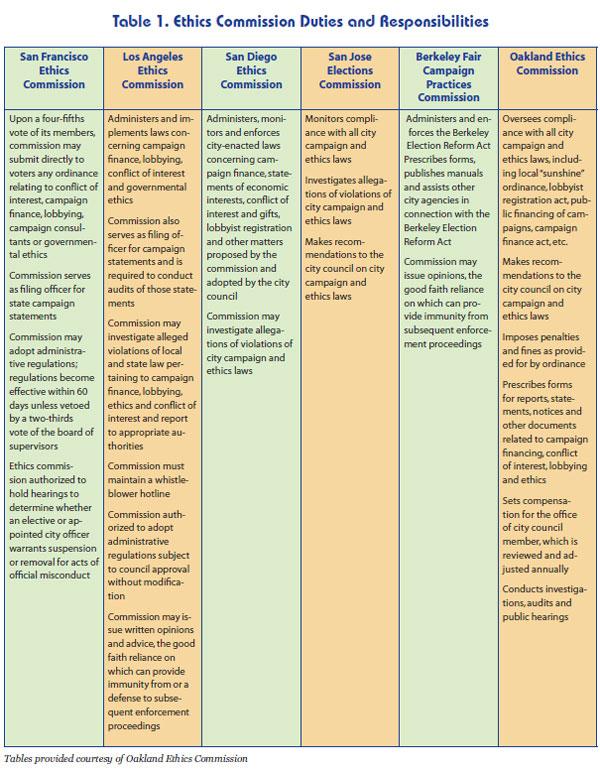

Most ethics commissions tend to focus on ethics laws as opposed to ethics (values-based conduct that goes above and beyond the minimum requirements of the law). See Table 1 for a list of responsibilities of various ethics commissions in California.

However, one California community experimented with having an ethics commission that enforced its values-based ethics code. The code had examples of what conduct reflecting certain values – such as fairness, trustworthiness, responsibility and respect – did and did not look like. The task assigned to the ethics commission in that situation was to assess whether a given conduct fell into the “does not look like” category.

How Should Members Be Selected?

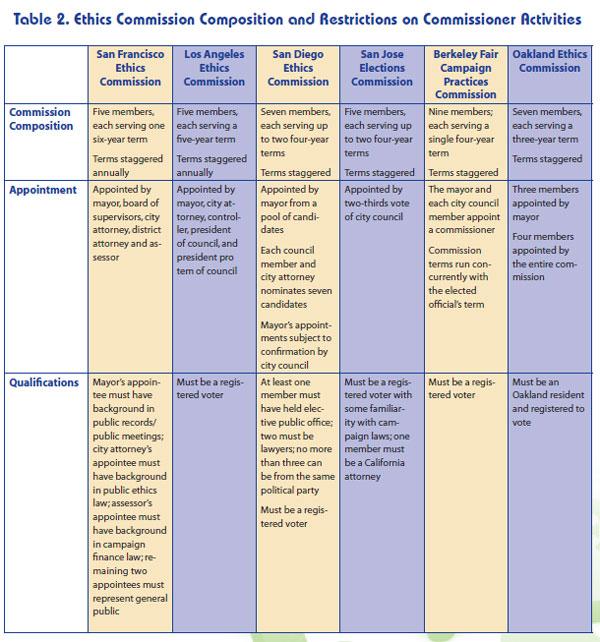

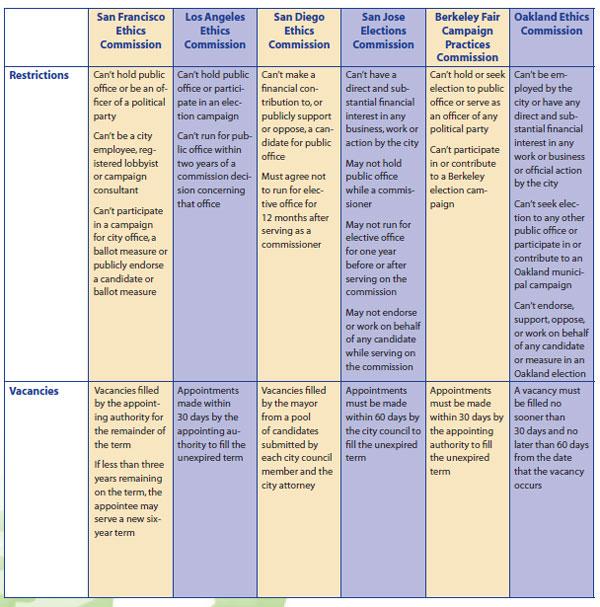

For an ethics commission to achieve the goal of promoting public confidence in its decision-making processes, it needs fair-minded and diligent members who are concerned with equitably enforcing its adopted ethics laws and requirements. This leads to the question of who appoints the members of the ethics commission. Table 2 illustrates how a number of jurisdictions have tried to achieve the goal of appointing fair decision-makers.

Public confidence in the commission’s decisions is also enhanced if the commissioners are not participants in the political process that they are charged with regulating. For that reason, a number of jurisdictions impose restrictions on commissioners’ participation in elections (see Table 2).

What Powers Should the Ethics Commission Have?

Other key decisions that will have to be made in the process of creating an ethics commission are:

- What kind of power should the commission have?

- Will the commission have the power to investigate claims of violations? and

- Can it subpoena records and compel people to testify before the commission?

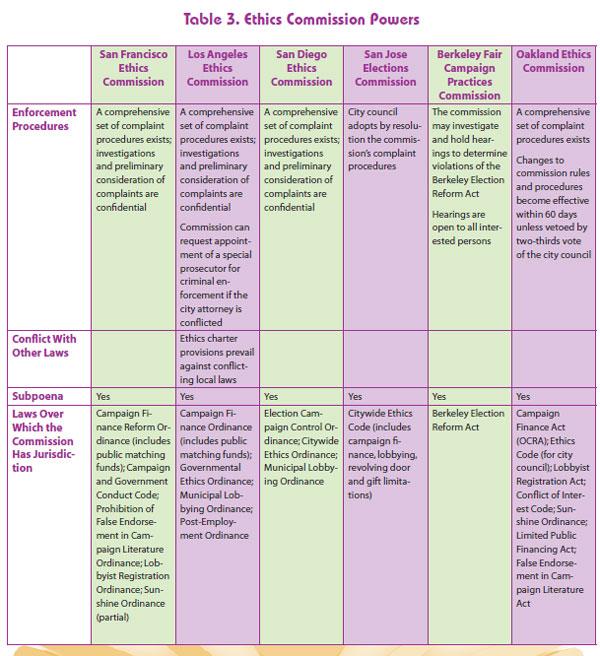

If the commission’s primary function is to enforce ethics requirements, the commission will typically be given the power to impose penalties (usually fines) for violations of laws within its jurisdiction. It may also be given the power to issue orders compelling compliance with ethics laws or enjoining violations. Table 3 explains how various jurisdictions answer these questions.

What Resources Are Available To Support an Ethics Commission?

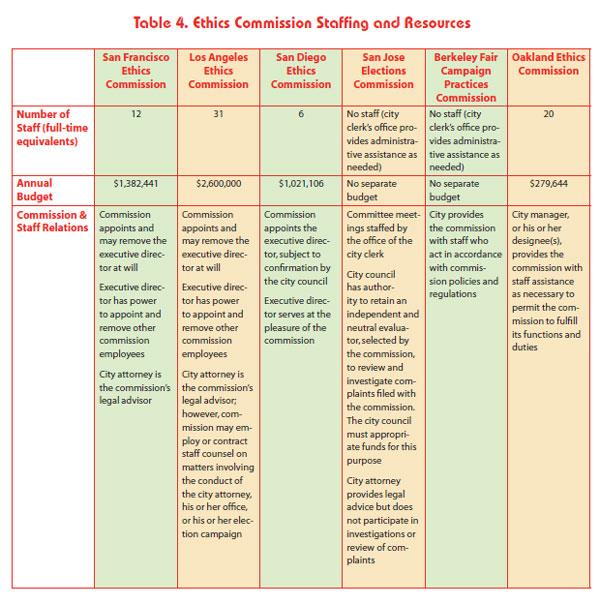

The commission will typically need staff to assist with its work. The Los Angeles Ethics Commission employs 31 people, but staffing levels vary. Table 4 shows how various ethics commissions are staffed and their associated budgets.

It’s also important to understand that indirect costs will be associated with supporting an ethics commission. Ethics commission staff will likely work closely with the agency counsel’s office and possibly with the agency auditor. For example, in Berkeley, the city clerk’s office also provides administrative support to the ethics commission.

Is an Ethics Commission Right For Your Jurisdiction?

A variety of decision-making processes are used to decide whether a community needs an ethics commission. Some jurisdictions assign the task of making recommendations on these issues to an ethics committee or task force. The task force’s recommendations are presented to the city council or board of supervisors, who then evaluate whether these recommendations should be adopted, adopted with modifications or subjected to further study and analysis. In charter cities and counties, the proposal may be put before the voters as a charter amendment. Voters can also use the initiative process to propose a matter for the ballot.

Another option is for community groups to collaborate with a local agency on a ballot measure. This hybrid approach helps create a proposal that reflects community concerns as well as the technical expertise of the public agency about how to craft a measure that addresses such concerns.

Conclusion

Local agencies have a number of tools available to them to promote a culture of ethics and compliance with ethics laws in their jurisdictions. An ethics commission is one such tool. Like all tools, there are tasks that ethics commissions can perform well, while other ethics-related functions may be better achieved by other measures. For more information about the range of tools available to local agencies to promote ethics in public service, visit the Institute for Local Government’s Ethics Resource Center at http://www.ca-ilg.org/ethics-codes.

Types of Ethics Entities

The following nomenclature may be helpful to underscore the differing roles that ethics-related positions or bodies can play in an organization, although different organizations may use different terminology.

Ethics Task Force

A body convened by a local agency to accomplish a specific task relating to ethics, typically making policy recommendations on ways to enhance the culture of ethics in an agency. The task force is usually disbanded after it has made its recommendations or accomplished its task.

Ethics Committee

A standing body designed to be a source of advice on policy implementation and support for ethics within the agency. An ethics committee can also play an educational role within the agency and out in the community.

Ethics Hotline/Ombudsperson

A sounding board for public officials on public service ethics dilemmas. In the private sector, many large companies provide such a source of advice for their people. This kind of position can also play an educational and training role.

Ethics Commission

A standing body with delegated authority to interpret and enforce the jurisdiction’s ethics regulations. An ethics commission can also play a role in training and education.

There Ought to Be a Law — Wait, There Is One!

Sometimes a jurisdiction will find itself evaluating whether to form an ethics commission or other ethics-related entity when it is experiencing a scandal. Leaders may feel under pressure to “do something” to prevent future scandals. To respond effectively, it can be helpful to identify exactly what caused the scandal to occur and tailor the response accordingly.

Sometimes the scandal will be that someone is charged with violating an ethics law. Under such circumstances, the solution may not be more laws or even more law enforcement. The solution may be stepped-up training. Such training may be helpful if the prevailing sense is that someone made an ignorant mistake (either not knowing something was against the law or not realizing the consequences of getting caught). Greater attention to creating a culture of ethics within the jurisdiction and sensitizing the voters to the need for considering ethics as a criteria in elections may also be solutions (see “Santa Clara infuses Ethics Into Campaigns” regarding the city’s “Vote Ethics” efforts).

In other cases, there may not have been a perceived violation of the law but a perceived lack of enforcement. If this is the situation, keep in mind that there may be multiple enforcement mechanisms. For example, the Political Reform Act allows for private enforcement if the Fair Political Practices Commission does not take action on a complaint. Moreover, under the federal law that protects the public’s right to “honest services” from its public officials, many violations of state ethics laws can also be prosecuted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office as a form of mail or wire fraud (or if money was involved, even income tax evasion).

Alternatively, the scandal may be that someone did not engage in conduct that should necessarily send them to jail or cause them to pay a fine; they just exercised very poor judgment. Or it could be a form of conduct that is very difficult to regulate (for example, issues related to free speech). This is where an aspirational, value-based code of ethics can help, particularly if it is accompanied by a well-defined, consistently implemented program to highlight the importance of the code as a guide for everyday conduct by public officials that reflects the community’s expectations. Visit www.ca-ilg.org/ethicscodes for more information on this approach.

In short, it’s important when facing demands that one “do something” about an ethics issue to choose a course of action reasonably tailored to fixing the problem that gave rise to the issue. Otherwise, one faces the specter of further erosions of the public’s trust and confidence if a remedy, while well-intended, proves ineffective in preventing a repeat occurrence.

This article appears in the December 2007 issue of Western

City

Did you like what you read here? Subscribe

to Western City