An economic engine: San Diego works to support its local creative industry during the pandemic and beyond

Jonathan Glus is the executive director of the city of San Diego’s Commission for Arts and Culture; he can be reached at jglus@sandiego.gov.

Six months into the pandemic, it was clear that San Diego’s creative industry was suffering. By September 2020, 14,500 local artists, photographers, dancers, filmmakers, graphic designers, architects, and computer programmers had lost their jobs. San Diego’s creative industry reported $96 million in lost revenues, upwards of four in 10 employees furloughed or laid-off, and a decline of $2.1 billion in economic impact.

The city of San Diego knew it had to act quickly and purchased 100 pieces of visual art by area artists. This is the largest such acquisition in the city’s history — in part to expand the city’s collection for use in public facilities, but primarily to get badly-needed funds to working artists.

That acquisition, called SD Practice was coupled with Park Social, a citywide temporary art initiative that will bring 18 unique installations and experiences to parks of all sizes throughout the city. This will directly benefit nearly 120 artists of all disciplines and will enhance the way San Diegans experience public spaces post-pandemic.

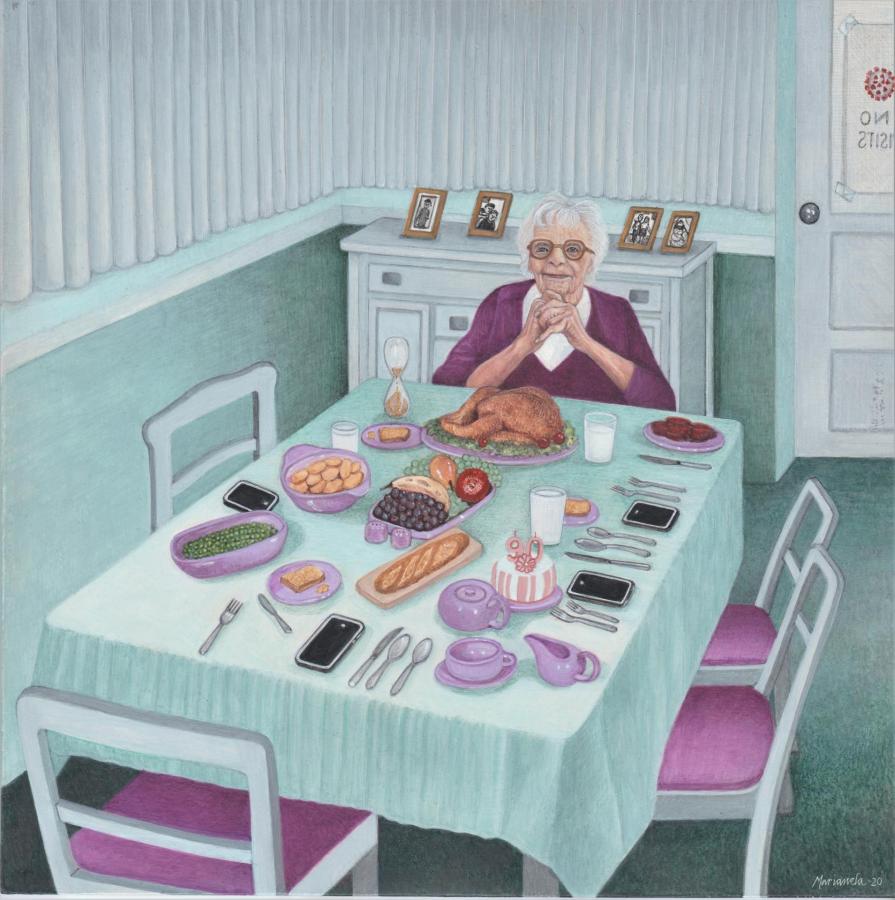

“The pandemic has been a difficult time for all of us. As an artist, every show I had scheduled was canceled or postponed,” said Marianela de la Hoz. “My work is not an object of easy sale, sometimes because of the strong themes I depict. Also because of the egg tempera technique I use, my production is limited and the average time it takes me to paint one of my small works is one month. I felt honored and relieved when the city acquired my painting. It gave me a break so I could continue with my paintings and hope for a better future.”

Anecdotally, the city knows that much of the creative sector has quickly pivoted during this past year, as the use of technology has shifted visual engagement and communications, event production, cultural experiences, and more to online platforms. An extraordinary byproduct is the global reach. New theater, dance, and music audiences have been developed and sustained in Asia, Europe, Africa, and most specifically, South America. The arts experiences present a tremendous branding opportunity that ties directly to tourism and business development.

Here at home, the longtime issues of access and equity to cultural experiences due to transit and financial barriers have been greatly reduced for residents across the region. Virtual platforms have allowed for much of the industry to pilot new programming, scale content, partner differently, and intentionally work to develop new audiences and customers who may not otherwise have been engaged.

Prior to the pandemic, the city wanted to understand the importance and intersection between San Diego’s creative industries and the local economy. San Diego’s first creative economy study was conducted in late 2019 and early 2020, by the San Diego Regional Economic Corporation on behalf of the city of San Diego, with additional research by University of California at San Diego.

The study spans 71 industries and 77 unique occupations that represent 4.5 percent of the regional economy. Broadly defining the creative economy as the combination of the nonprofit arts and culture sector and the for-profit creative industries, the total annual economic impact in San Diego was $11.1 billion before the pandemic hit.

The city of San Diego has long invested in the nonprofit arts and culture sector through transient occupancy tax-funded general operating grants, as well as grants for festivals and other special events. These funds have fueled the growth of iconic, San Diego-only cultural institutions such as the 19 museums, gardens, and performing arts organizations in the Balboa Park cultural district, global gatherings such as Comic-Con, and many of the city’s nearly 50 film festivals.

The strategy and measure of the arts and culture funding program has historically and primarily been one of investing in cultural infrastructure to increase and enhance one of the city’s largest industries, tourism. The argument is as clear today as ever — cultural tourism is good for the economy. Tens of thousands of tourists from across the world visit our cultural organizations each year, enhancing their experiences in San Diego and often extending their stay.

Tangential to the economic development and tourism case but critical to the community is the important role the nonprofit arts and culture sector plays in educational opportunities for public school children, anchoring neighborhoods and business improvement districts with cultural assets, and providing cultural education for residents outside of the highly visible tourism and cultural centers in the central city and beach communities.

For example, the city of San Diego also supports neighborhood-based and culturally-specific organizations such as The Front and Sherman Heights Community Center. The Front is a gallery and performance space that is a program of Casa Familiar, a community development organization in San Ysidro that provides affordable senior housing, artist studio spaces, health services, and more. With a view of the border, The Front has evolved into a primary cultural anchor to the binational experience shared by Tijuana and San Diego and a key contemporary art venue for the region. Another example is the Sherman Heights Community Center, which primarily serves San Diego’s Barrio Logan and adjacent areas. The Community Center is a highly-respected community anchor that embeds health and educational services into the cultural life of the neighborhood.

The long-held notion that investing in the nonprofit arts and culture sector guarantees investment in jobs remains true, but today, it is only a portion of the story. That is why the city needed to launch the more comprehensive creative economy analysis: jobs and a changing workforce.

San Diego’s creative economy study revealed that the larger creative sector employs more than 50,000 people, while inducing another 56,000, for a total of nearly 108,000 jobs. San Diego’s creative industries have a ripple effect throughout the entire regional economy, with every job in the creative sector — creative or not — supporting another 1.1 jobs across categories, which is nearly 7 percent of total regional employment. Digital media, entertainment, and publishing and printing make-up nearly two-thirds of the total economic value added by creative industries.

Of the 7,386 firms and organizations that make up the creative economy, the vast majority are small, with staff from one to 19. Importantly, 60 percent of creative firms and organizations routinely hire contractors of all types, from accounting and legal, to creative and artistic talent. In other words, the creative economy is the gig economy at work. Creative firms pick up professional consultants and contractors, as well as independent creative contractors and sole proprietors. Nonprofit arts and culture organizations rely on the creative gig economy for all facets of their work, from teaching artists, museum educators, docents, and communications.

The city also supports the La Jolla Playhouse, an important regional theatre based on the campus of the University of California at San Diego. Founded in 1947, the Playhouse has produced 84 world premieres, 32 West Coast premieres and eight US premieres, winning hundreds of honors over the years, including the Tony Award for Outstanding Regional Theatre. The Playhouse has sent 33 of its productions to Broadway, making it, along with the Old Globe Theatre, one of the country’s premier local generators of national talent.

Along with the more than 50 other San Diego nonprofit theaters, the Playhouse relies on a robust local creative economy. Local talent, including production hands, lighting designers, professional dancers and actors, costume designers, choreographers and composers, musicians, set designers, and builders, are a fraction of job types that are hired or contracted to deliver each production. Graphic design intersects with fashion design and videography. Design thinking continues to be integrated into the innovation of technology.

Building and sustaining a cultural and creative ecosystem is a key component to today’s urban economy. With the educational entry point less than many other industries and the average salary for a creative worker at $75,000, a career in the creative workforce is a solid path into the new-economy middle-class. The flexibility of working across sectors, from nonprofit theatre to video production, and software design, reflects the way Americans work. As we move out of the pandemic, both the profit and nonprofit sides of the creative economy will be driven by a creative workforce with even greater skills to reach customers, engage audiences, and reinforce San Diego’s identity as a creative engine.