Hot Topics in California Municipal Finance

Michael Coleman is principal fiscal policy advisor to the League and can be reached at coleman@muniwest.com. More information on city finance is available at www.californiacityfinance.com. Michael Colantuono is a shareholder in Colantuono, Highsmith & Whatley, PC, a municipal law firm with offices in Pasadena and Grass Valley. Colantuono is city attorney for the cities of Auburn and Grass Valley; he can be reached at mcolantuono@chwlaw.us.

At the recent League of California Cities 2018 Annual Conference & Expo, attendees learned about several new developments in the financing of municipal services in California. The many important things to know about the current state of local government finance include these items:

- The state’s finances have improved substantially over the past six years, and constitutional protections for local revenues are in effect. These two factors reduce local governments’ risks of losing revenue through budgetary takings, shifts and “swaps” by the state — particularly when the next economic downturn comes;

- The U.S. Supreme Court decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., in June 2018 favored local governments and will improve fairness among retailers and collection of sales and use taxes at the state and local levels; and

- A California Supreme Court decision in Citizens for Fair REU Rates v. City of Redding in August 2018 provides helpful support for transfers from municipal utilities to municipal General Funds, although other important questions related to this issue remain to be answered.

California’s Improved Financial Condition is Good News for Cities

California’s General Fund revenues plunged from more than $100 billion in 2007 to roughly $85 billion in 2008 — mostly due to declines in revenues from the state personal income tax and sales tax. The state’s General Fund revenues are highly volatile compared with those of local governments and other states. Because California’s progressive income- tax structure levies increasingly higher marginal tax rates on higher-income earners, economic changes quickly and dramatically impact state government revenues. Managing higher volatility and uncertainty requires stronger reserves and careful budgeting to avoid overcommitting to ongoing spending and instead favoring capital investments, building reserves and paying down debts.

In recent years, California voters have approved a number of ballot measures that have strengthened the state’s financial management and position. These include:

- Proposition 2 (2014), which fortified the state’s rainy day reserve and debt pay-down rules;

- Prop. 30 (2012), which provided about $6 billion per year over seven years. This was funded with additional upper-bracket income taxes and a temporary sales tax. (California voters in November 2016 passed Prop. 55, continuing the higher personal upper-income tax brackets through 2030. Single-filers earning more than $263,000 and joint-filers making more than $526,000 pay a 10.3 percent tax on their upper income and those making more than $1 million will pay 13.3 percent. The Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates that these higher tax rates raise $4 billion to $9 billion a year); and

- Prop. 25 (2010), which allows the Legislature to pass a budget with a simple majority and suspends legislators’ salaries if they fail to meet the constitutional June 30 deadline to adopt a budget.

Remarkably, since the passage of Prop. 25, the Legislature has passed balanced, on-time budgets, creating greater financial certainty for local governments at the outset of each budget year. More importantly, since the passage of Prop. 30, the state has largely erased its budgetary borrowing debt (interfund borrowing, deferred reimbursements and other maneuvers) that once perilously totaled over $35 billion.

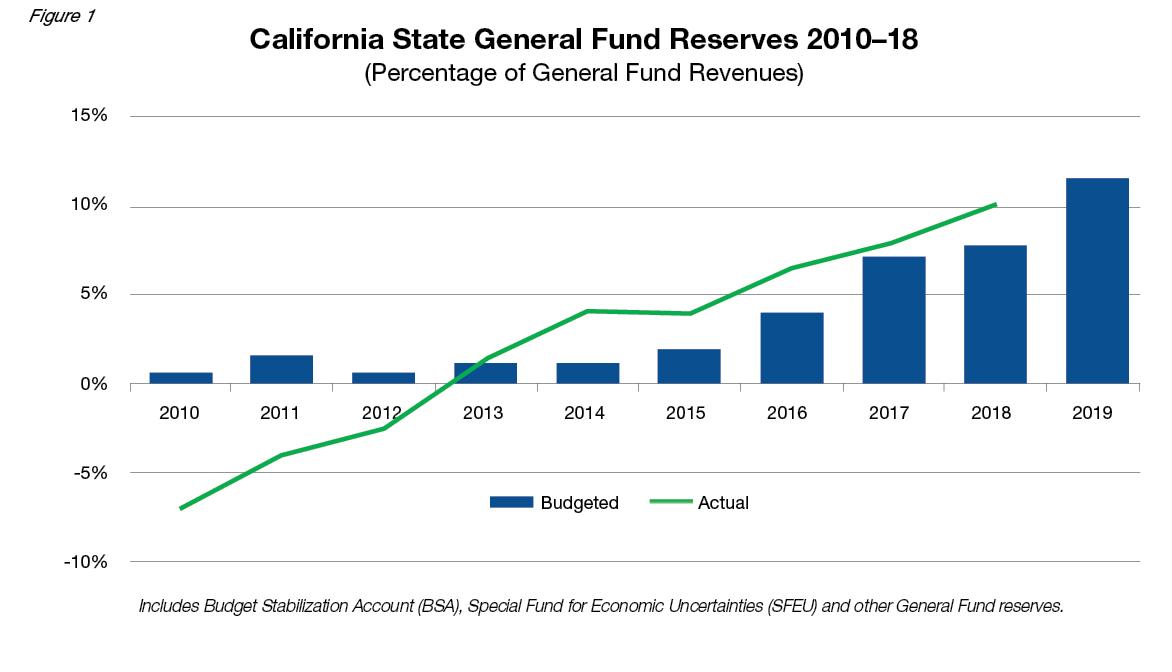

And California has steadily built up its General Fund reserves to nearly 12 percent of annual revenues (see Figure 1, below). This now puts California well above average among the 50 states and among the top 10 for healthy General Fund reserve levels.

The next recession may be just around the corner, but the state is much better positioned to weather it — and that bodes well for local governments dealing with their own financial challenges.

Constitutional protections further reduce the risk of actions by the state that might shift revenues and expenses. Prop. 1A (2004) and Prop. 22 (2010) together prohibit the state from:

- Transferring responsibility to local government for a program the state previously fully or partially funded;

- Reducing the local Bradley-Burns Uniform Local Sales and Use Tax rate;

- Shifting property taxes from cities, counties or special districts; and

- Shifting locally approved taxes away from taxing agencies.

U.S. Supreme Court’s Wayfair Decision Levels the Playing Field

In June 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a long-anticipated decision in a dispute about the collection of sales tax revenues from out-of-state e-commerce retailers in South Dakota v. Wayfair. Unlike an over-the-counter transaction where the collection duty, tax rate and allocation of a sales tax is straightforward, a “remote sale” — which includes online transactions, telephone orders, mail orders, etc. — involves a purchaser and seller in different locations and is more complex. In the case of a transaction where the seller is located out of state with no in-state physical presence (such as a warehouse or sales office), the U.S. Supreme Court previously ruled that a state cannot compel the retailer to collect a tax due on the transaction. In California, as in other states, this has meant the purchaser is responsible for payment of use tax on the transaction. Businesses, audited for compliance by state taxing agencies, pay about 90 percent of use tax due in California. But consumers are much less likely to report and pay use tax that the retailer fails to collect. The growing volume of business-to-consumer sales by out-of-state retailers means an increasing amount of uncollected taxes. This particularly affects states like South Dakota and North Dakota, where sales tax revenues are especially critical revenue sources and where retail businesses are less likely to have a physical presence than, say, California, Texas or New York.

Under the 1992 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, a state could not compel a seller to collect state sales taxes if it had no property or employees in the state. The court signaled that Congress could compel out-of-state retailers to collect tax. But over the several decades since then, Congress has not come close to acting on the issue. Many retailers argued that the physical presence rule gave out-of-state sellers an unfair advantage.

South Dakota officials, acting in overt and intentional conflict with the 1992 decision, sought to force out-of-state retailers Wayfair, Overstock and Newegg to collect sales taxes on purchases by South Dakotans. They sensed that some members of the U.S. Supreme Court had grown impatient with Congress’s inaction and had begun to believe that in today’s digital economy, a retailer that does substantial business in a state has a business presence there even if it has no offices or employees there.

In a 5-4 decision, the court agreed with South Dakota and overturned Quill. The court held that the physical presence rule, as first formulated and as applied today, is an incorrect interpretation of Congress’s power under the so-called Dormant Commerce Clause to regulate taxation of interstate commerce. The decision noted that South Dakota limited its tax requirement to vendors with $100,000 in receipts or 200 transactions per year and its tax is therefore not an undue burden on interstate commerce, but signaled that requirements for smaller entities with fewer transactions in South Dakota might be unduly burdensome. As former Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion states:

South Dakota’s tax system includes several features that appear designed to prevent discrimination against or undue burdens upon interstate commerce. First, the Act applies a safe harbor to those who transact only limited business in South Dakota. Second, the Act ensures that no obligation to remit the sales tax may be applied retroactively. S.B. 106, Section 5. Third, South Dakota is one of more than 20 states that have adopted the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement. This system standardizes taxes to reduce administrative and compliance costs: It requires a single, state-level tax administration, uniform definitions of products and services, simplified tax rate structures, and other uniform rules. It also provides sellers access to sales tax administration software paid for by the state. Sellers who choose to use such software are immune from audit liability.

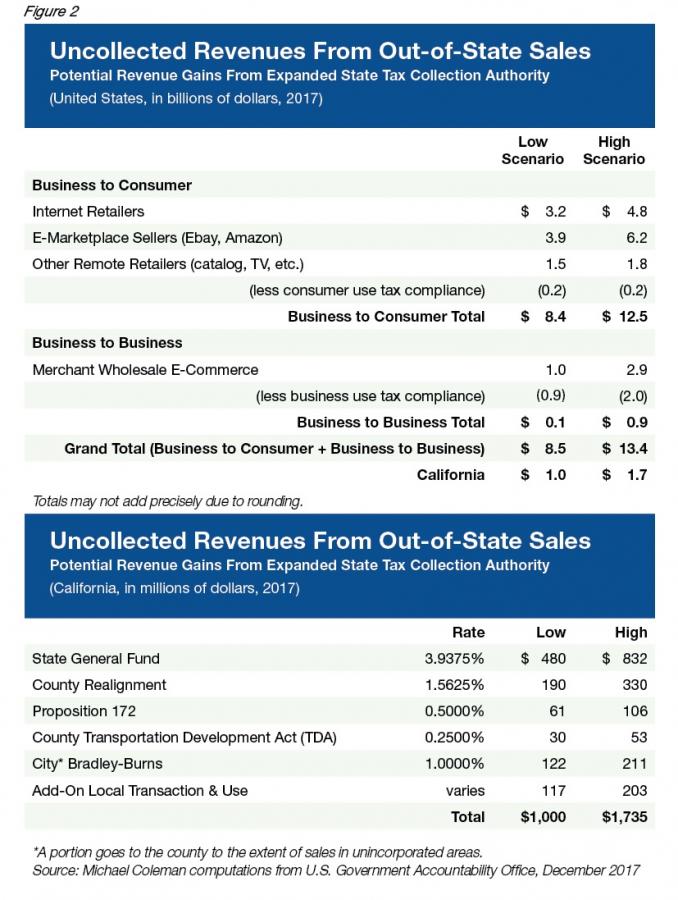

California has not yet implemented collection of out-of-state taxes under South Dakota v. Wayfair, as its tax agencies and legislators are pondering the best way to do so. Nevertheless, the financial gain to California’s state and local agencies may be less than some suppose. Unlike in the Dakotas and other smaller states, it is more common for a business to have a physical presence in California and thus many may already be collecting and remitting sales tax as in-state businesses. Based on a recent study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, California’s growing annual uncollected sales tax revenues from out-of-state transactions totaled somewhere between $1 billion and $1.7 billion in 2017. Most of this comes from business-to-consumer transactions, rather than business-to-business transactions. Applying these estimates, the local Bradley-Burns 1 percent sales tax would be between $122 million and $211 million per year, about 2 to 3 percent of current Bradley-Burns allocations.

California Supreme Court Provides Helpful Support for Limited General Fund Transfers From Municipal Utilities

Cities commonly transfer funds from their enterprise utilities to their General Funds. These transfers are often made as payment for services provided to the utility by General Fund-supported departments such as finance, information technology, personnel, legal and administration. In some cases, such as with the City of Redding’s electric utility, the transfers are payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) or franchise fees. Not only do these transfers compensate for costs of services provided to the utility and its customers, but they also allow the municipal utility to contribute to the community’s tax base just as a private utility would.

Such transfers were invalidated for water, sewer and solid waste under Prop. 218 (1996); (see 2002 Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association v. City of Roseville and 2005 Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association v. City of Fresno). But Prop. 218 expressly exempts fees for gas and electric service from its rules for so-called “property-related fees” — an exception apparently intended to preserve lifeline rates for low-income seniors, a constituency important to Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association.

In November 2010, California voters passed Prop. 26, a tax- and fee-limitation measure sponsored by business interests. Prop. 26 defines all local government charges as taxes requiring voter approval unless one of seven stated (and two implied) exceptions applies. Among the exceptions is a “charge imposed for a specific government service or product provided directly to the payor that is not provided to those not charged, and which does not exceed the reasonable costs to the local government of providing the service or product.” Thus, Prop. 26 limits gas and electric rates to the cost of service.

In December 2010, residents sued to challenge Redding’s electric utility rates as non-voter approved “taxes” under Prop. 26, claiming the rates funded the city’s PILOT and therefore necessarily exceeded the cost of service. The California Supreme Court ruled for the city, noting the record showed that the utility’s nonretail-rate revenues were sufficient to cover the PILOT and therefore the challengers could not show that retail power rates fund it. The Supreme Court treats revenues from wholesale transactions as unrestricted and not “imposed” on anyone, as participants in wholesale power markets are willing sellers and buyers. All of California’s initiative restrictions on local government finance — Propositions 13, 62, 218 and 26 — apply only to revenue measures that governments “impose” by compelling people to pay them.

This means local governments may now maintain PILOTs and other transfers from power utilities — to the extent those transfers do not exceed nonretail-rate revenue — without violating Prop. 26.

The decision may have broader, helpful implications for local government revenue authority. The court helpfully states that the “no free-riders” rule of Prop. 26 is not violated by a fee that not all customers pay or if some customers pay more than others without a cost differential — provided there are non-fee revenues to cover the difference. The court also stated that non-rate, discretionary revenues (such as rents, wholesale sales, royalties, etc.) need not subsidize retail rates: “such subsidization is not required by California law.” The state Constitution “does not compel a local government utility to use other non-rate revenues to lower its customers’ rates.”

Outstanding Questions Remain

The case did not decide two questions of vital interest to local governments:

- Does Prop. 26 grandfather local legislation that predated it and that imposes costs on the utility that are not costs to generate, store and distribute power? This will affect not only General Fund transfers, but also such things as “public goods charges” that fund conservation and clean-energy programs and discounted rates for low-income and senior households.

- Does Prop. 26 allow the theory that a PILOT is a reasonable service cost because it approximates costs a private utility would pay?

Further developments in this area of the law are likely.

Conclusion

Prop. 26 cases have been coming down from the appellate courts in rapid succession over the past two years and more are in the offing. This area of the law is developing rapidly, and California state and local ratemakers should be alert for further developments.

SB 231 and Storm Sewer Fees

by Michael Colantuono

Many cities are grappling with the challenge to fund compliance with expensive mandates under the federal Clean Water Act to improve the quality of runoff from city streets. These involve both expensive capital projects (catch basin inserts, bioswales, etc.) and intensive maintenance and operation expenses (like cleaning those catch basin inserts, inspecting private land uses, etc.). Conceptually there are four ways to fund these efforts: taxes, assessments, fees, and subventions from the state and federal governments.

Taxes require voter approval and a tax limited to water quality and/or flood control would be a special tax requiring two-thirds voter approval. Some cities — often in coastal communities —have succeeded in gaining approval of these taxes. Assessments require majority approval of property owners voting in a Proposition 218 mailed ballot “protest” proceeding. These, too, have had more success in coastal than inland communities. Grants and other subventions are not nearly enough to cover these costs. That leaves fees.

Fees on private parties to fund inspections and regulation of land uses that affect water quality are straightforward and noncontroversial. A fee on a restaurant to inspect to make sure it does not hose off kitchen mats in the parking lot can be imposed without property owner or voter approval and cover these costs of these regulations. However, regulatory fees will not fund a city’s own capital and maintenance and operations expenses. Thus, many communities have considered fees on residents and property owners. These are most often property-related fees subject to Prop. 218.

Property-related fees require a noticed protest proceeding at which those who are to pay a fee collected on the property tax roll or otherwise as an aspect of property ownership may protest. If a majority of those subject to a fee protest in writing in a 45-day notice period, the city cannot impose the fee. Such protests proceedings have become familiar with respect to water, sanitary sewer and solid waste fees — and majority protests are rare, because majority participation in public life is rare, much less in writing and on 45 days’ notice. However, for fees other than water, sanitary sewer and trash services, Prop. 218 also requires an election — seeking a majority of property owners voting in a mailed ballot election or two-thirds of registered voters voting at the polls. This second step makes a tax more appealing than a property related fee — why conduct both a protest hearing and an election if you can just hold an election?

In 2002, the San Jose Court of Appeal decided in a case involving Salinas that the “sewer” fees that can be approved after a protest hearing and without an election were limited to sanitary sewer fees and excluded fees to fund storm sewers. Several efforts were made to amend the California Constitution to reverse that result in the next several years, but none could achieve the necessary two-thirds support in the Legislature. Senator Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys) introduced SB 231 to disagree with the Salinas decision by ordinary statute and Gov. Brown signed the bill into law (Chapter 536, Statutes of 2017). It amends the Prop. 218 Omnibus Implementation Act of 1997 to define “sewer” to include both sanitary and storm sewers. The statute took effect on Jan. 1, 2018 but has not yet been relied upon by an agency to justify a storm sewer fee.

Ordinary legislation, of course, cannot amend the state Constitution. And court of appeal decisions bind all trial courts in California until the Supreme Court disapproves them or another court of appeal publishes a decision disagreeing with them. Thus, taking Salinas off the books will require litigation. Test litigation is likely, and cities would be wise to consult with legal counsel before attempting such a fee. Sen. Hertzberg’s office has provided support for local agencies considering it; slides discussed at a panel discussion on the topic are available on his website at https://sd18.senate.ca.gov/sites/sd18.senate.ca.gov/files/sb_231_webinar.pdf. The video can be found at https://sd18.senate.ca.gov/sb231-webinar.

The outcome of this effort will become known over the next few years as test litigation arises and works its way toward an appellate decision.

The State’s Refusal to Fix the VLF Swap Discourages New City Incorporations and Annexations

by Michael Coleman

The state Vehicle License Fee (VLF) was for decades a significant source of funding for cities, typically providing 5 to 25 percent of general revenues. The Legislature adopted the VLF in 1935 in lieu of the taxation of motor vehicles in the local property tax system.

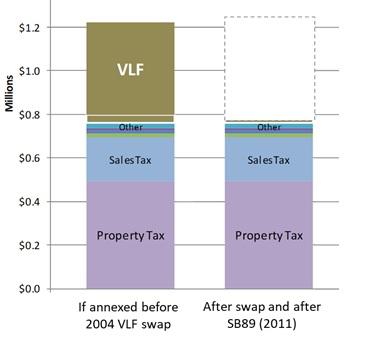

In 2004, the California Legislature approved a swap of the VLF for property tax as a part of the state budget agreement. The swap eliminated a state General Fund backfill to cities and counties that since 1998 had paid cities and counties for their revenue loss from state VLF rate cuts. Instead, cities and counties received greater property tax share. But the 2004 swap legislation failed to provide compensating property tax revenues to city annexations and new city incorporations. The substantial revenue loss effectively halted new incorporations and annexations of inhabited areas.

In 2006, Gov. Jerry Brown signed AB 1602 (Laird) that provided special allocations, carved from the remaining city VLF revenues, to new incorporations and annexations. These VLF allocations supported state Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) policies that encourage service consolidation, including the annexation of “islands” of inhabited unincorporated territory. But in 2011, in conjunction with a hastily crafted annual budget bill, the Legislature redirected these revenues to fund state law enforcement programs that had previously been funded by the state.

Virtually all annexations of urbanized areas and new city incorporations have been made financially unfeasible by the loss of huge amounts of revenues that previously would have gone to these areas. This undermines state policies intended to steer urban development away from sensitive habitats and prime farmland and achieve sustainability, greenhouse gas reduction, smart growth, infill and transit-oriented development.

No Property Tax in Lieu of VLF Makes Many Annexations Financially Unviable

Helpful Background: VLF and New Annexations

- Prior to the VLF Swap of 2004, VLF revenues were collected and allocated statewide among cities and counties. When a city annexed an area, the population residing in the annexed area would result in additional VLF revenue to the city.

- The VLF Swap of 2004 excluded city annexations from growing city property-tax-in-lieu-of-VLF amounts (referred to in statute as a “VLF Adjustment Amount”). Only growth on assessed valuation after annexation would boost the city’s property-tax-in-lieu-of-VLF. This severely disincentivized annexations of already developed (inhabited) areas.

- A special allocation to compensate annexations was eliminated in 2011 when the state wiped out remaining city VLF revenues with SB 89 (Chapter 35, Statutes of 2011). 140 annexing cities lost revenues and annexations again became fiscally discouraged.

Legislation to fix the annexation VLF problem has been vetoed by the governor or stymied in legislative appropriations committee citing costs to the state.

SB 130 (Roth) of 2017 Fixed the Four Newest Cities

When the Legislature abruptly shifted remaining city VLF allocations in 2011, four newly incorporated cities were suddenly thrown into financial peril. Finally, in 2017, Gov. Brown signed legislation providing these cities with property tax in lieu of VLF like every other city in California. But the problem has not been fixed for future incorporations or for annexations.

Photo Credit: Busracavus (Coins), MarsYu (Graph), PPAMPicture (Building).